It's been six months. Time for revisiting AI.

At least one think tank projects that the next two years will usher in the real revolution in superintelligent agents that can out performs armies of us humans. If it's right, strap in.

A topic that almost rivals the machinations in Washington is artificial intelligence. I’ve dedicated two newsletters to it, the most recent last fall, “AI is for Real. Accept it.” However, developments in the AI world come along in bursts. Six months in AI development is like the Pleistocene Age to human evolution. So it’s time for number three.

The impetus was the flurry of commentators irecently in The New York Times, Wall Street Journal, and Boston Globe, among others, all dealing with the issues AI that have been raised since ChatGPT was unleashed in 2023

What is AI?

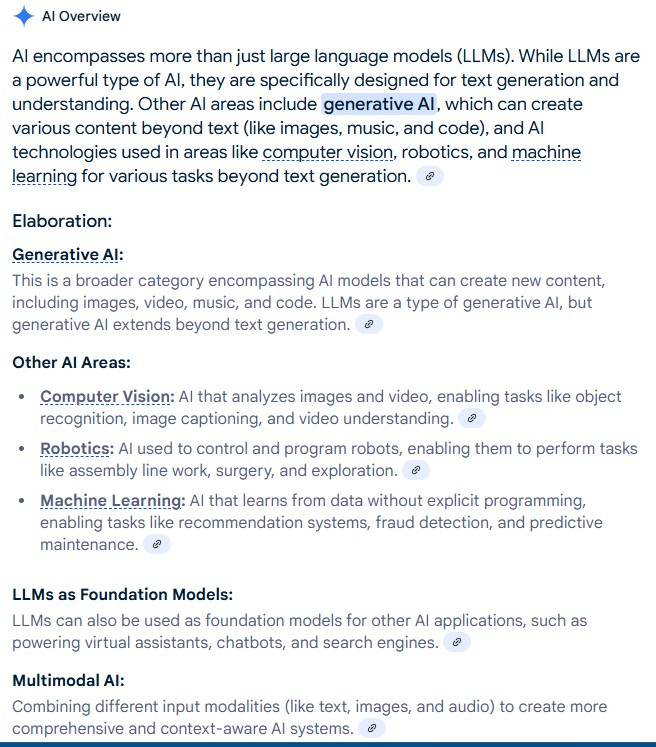

Perhaps I should take a step back to be sure we are working from the same concept of artificial intelligence.

AI encompasses a broader range of technologies than just large language models. (LLMs). While LLMs excel at understanding and generating human language, AI also includes diverse fields like machine learning, computer vision, and robotics. These fields tackle different problems and utilize various techniques, making AI a multifaceted discipline.

That previous paragraph I cribbed from a Google search asking, “What is AI in addition to large language models?” Rather than return links to several articles about Google's recent announcements about Gemini, its AI application, the top response, seen below, was an AI-created synthesis of material on the Web—but in its own language rather than just quite from those articles. (This might be difficult to see if you are using your phone to read the Pancake.)

Chatbots and Agents

Chatbots today can be very frustrating, but I do see signs that some are improving with AI. If you’ve been directed to use a “virtual agent” for customer support, either online or on the phone, you’ve experienced how frustrating that can be: “Hi, I’m Florence. How can I help you?” “Me: “My [name device] is not working.” It: I understand the [device] is not working. Is there electricity on in your building?” (I swear this was a question in the troubleshooting section of a real instruction manual.) It: “Is the [device] plugged in?” (Another real question).

However, I recently had this interaction with a chatbot: Me: “The battery in the charger is not charging.” It: “Tell me what steps you have taken.” “Me: “I unplugged the charger and plugged it back in again. I also reset the charger.” "It: You likely need a replacement charger. I see you are under warranty. I will have an agent contact you to arrange a replacement.” Me: “Thank you.” (I don’t know why I had to be polite to a chatbot. It: “Is there anything else I can help you with?” Me: “Sure. Can you rake the leaves on the patio?” (That’s what I was tempted to say, but I just said no and signed off.)

A few minutes later, I received an email (from Manual, I think, but maybe it was Florence under an alias). It confirmed my shipping address and said that the replacement charger was being processed. A tracking number followed.

In this case, the chatbot was making use of both language and logic, and likely machine learning. That is, as a result of numerous similar encounters about charger problems, the system learned that given a certain set of symptoms and knowing from my login that I was under warranty, it was able to determine the remedy. In the past, that may have had to be passed on to a human agent. A customer out of warranty may have been offered the option of purchasing a charger.

Beyond chatbots are AI agents, which may be thought of as an employee who works from home, except that the worker is virtual. You can talk with it—think Siri— and give it a task, such as write a legal brief for a particular case, analyze financial records, or arrange for a venue and refreshments for an event. It might ask some questions, e.g., how many people and what your budget is for the event. It will go off and, depending on complexity, do that task. In 10 minutes or an hour, it will have completed the task.

Manus, a Chinese start-up, now offers a preview of the future. Manus is an “agentic AI” system designed to perform complex actions while needing far less human control. Ask Manus to do something, and its AI-trained software agents develop their own plan to give you what you want with minimal human involvement.

To test it, I was interested in communities in the Portland, Maine area restricted to those at least 55 years old. I Googled that. Within a second, Gemini first summarized that there were “several” such communities, naming three. It added that there was one for low-income. Then it provided links to each.

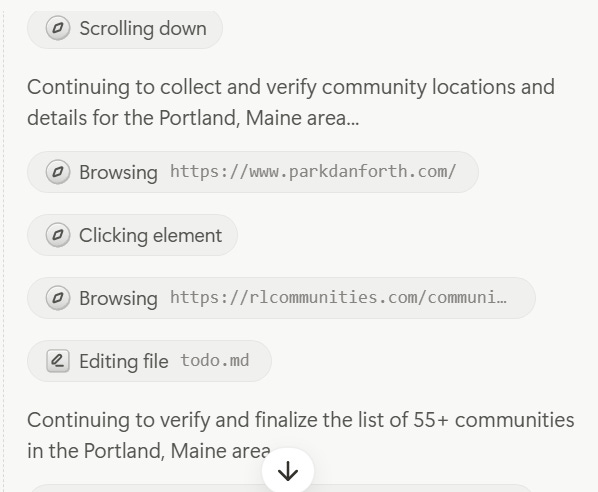

On the other hand, Manus spent about five minutes with the query. As I waited, it showed me it’s “thinking,” identifying websites it was checking out, and processes it was undertaking, such as below:

When it was finished, it provided a map, which I hadn’t specifically requested, and a summary of the task list it created from my simple query. I could have developed this map after researching the names and locations of these communities, but Manus did in 10 minutes what might have taken even an experienced Web developer hours.

Finally, Manus offered to create a permanent Website with its report, so I could share it. I took it up on this option. The first URL it provided did not work. I informed the AI: “The Website you just created did not work.” Its initial response was “I apologize for the issue with the website. Let me investigate what went wrong and fix it immediately. I'll check the deployment and make sure everything is working properly.” It reported on each step: checking, verifying, and debugging JavaScript. At one point, it explained:

I'm still experiencing issues with the website deployment. The site is not displaying the map and community list as intended. Let me take a different approach to ensure you get a working website. Instead of continuing to troubleshoot the React deployment, I'll create a simpler but equally effective HTML/CSS/JavaScript website that will be more reliable for deployment.

After another five or 10 minutes, I saw “Great news! I've successfully created and deployed a fully functional website showing all 55+ communities in the Portland, Maine area. The website is now live at: https://cyghhlue.manus.space.” Check it out.

This demonstrates both chatbot and AI Agent applications. The process was something of a conversation. I was particularly impressed when the initial map didn’t work, and I pointed that out to the AI. It understood, reacted, and responded with new code, apparently understanding what didn’t work before and programming around that.

At the moment, Manus is slow compared to a Google search. However, it is easy to see that, as v1.0, it has the elements of an application that could be useful—and, as with all AI, potentially harmful. Issues that have been raised since ChatGPT was unleashed in 2023 are being realized, among them students using—or accused of using—AIs to write their papers or computer code, and professors who use AI to create their lectures and notes.

The real AI revolution is upon us in this scenario

What has most engaged me were several articles about Daniel Kokotajlo, an AI researcher who currently leads the AI Futures Project. Kokotajlo was a researcher in the governance division of OpenAI, the ChatGPT developer, prior to his current gig.

In AI 2027, Kokotajlo and colleagues write that they “predict that the impact of superhuman AI over the next decade will be enormous, exceeding that of the Industrial Revolution.” He sees AI improving exponentially. Essentially, that means that version 2.0 is twice as good as 1.0, that 3.0 is 4 times better, and that 4.0 is 16 times better. Where does that lead?

First, he said, sometime in early 2027, if current trends hold, A.I. will be a superhuman coder. Then, by mid-2027, it will be a superhuman A.I. researcher — an autonomous agent that can oversee teams of A.I. coders and make new discoveries. Then, in late 2027 or early 2028, it will become a superintelligent A.I. researcher — a machine intelligence that knows more than we do about building advanced A.I., and can automate its own research and development, essentially building smarter versions of itself. From there, he said, it’s a short hop to artificial superintelligence, or A.S.I., at which point all bets are off.

In this scenario, AI agents become similar to an employee who works from home, except that the worker is virtual. You can talk with it—think Siri— and give it a task, such as write a legal brief, analyze financial records, arrange for a venue, and refreshments for an event. It might ask some questions, e.g., how many people and what your budget is for the event. It will go off and do that task. In 10 minutes, it will have completed the task.

Well, maybe. What about plumbers and electricians and carpenters and waiters? An agent can’t replace them. Maybe not entirely, but the Kokotajlo scenario does address this. In an interview with New York Times columnist Ross Douthat, the futurist tried to shake us from our linear thinking.

They’re expecting that we have A.I. progress that looks kind of like it does today — where companies run by humans are gradually tinkering with new robot designs and figuring out how to make the A.I. good at X or Y — whereas in fact it will be more like you already have this army of superintelligences that are better than humans at every intellectual task. Better at learning new tasks fast and better at figuring out how to design stuff. Then that army of superintelligences is the thing that’s figuring out how to automate the plumbing job, which means that they’re going to be able to figure out how to automate it much faster than an ordinary tech company full of humans would be able to figure out.

Some of these outcomes are not new. What has changed here is the timeline. The “AI 2027” scenario believes that the impact of Artificial General Intelligence (or AGI in AI-speak) will be upon us far faster than has been generally envisioned, as a result of the exponential nature of the improvements in AI it foresees. The implications are massive productivity improvements, much shorter work weeks, yet with higher income. But there is also the possibility of widespread unrest and political repercussions that often come with rapid social change.

Kokotajlo does pull his punches a bit: “So, I feel like I should add a disclaimer at some point that the future is very hard to predict and that this is just one particular scenario. It was a best guess, but we have a lot of uncertainty.” However, for him, this means “it would probably be more like 2028 instead of 2027….”

The Kokotajlo scenario may be overwrought. It is certainly aggressive in its timeline. But don’t take comfort in stories of AI apparent fakes, such as the report last week that syndicator King Features, a service that produces comics, puzzles, and supplemental material. It provided an insert for newspapers filled with tips, advice, and articles on summertime activities. One section was a “Summer reading list for 2025.” The AI-generated feature recommended some titles and authors that were legitimate. Others, however, included real titles for nonexistent authors, and some real authors were credited with nonexistent titles.

Such so-called “hallucinations” have been widely cited as supposed evidence that AI-generated materials cannot be trusted, hence the need for human creators. However, you may also recall that the 1990s Windows 3.1 and Windows 95 often crashed and were unreliable. When was the last time you had a frozen Windows computer or the “blue screen of death”? We can’t extrapolate too far ahead with technologies.

How can we characterize the rate of improvement in generative AI platforms?

I asked that question of the latest Claude-4 AI model. Admittedly, asking an AI to describe its own development might seem circular. That said, after taking into account the warning from its developers that Claude can make mistakes, the response was consistent with my own expectation, for what that’s worth.

For one, it offered the recognition that many improvements appear as sudden capability jumps rather than smooth curves. Hence, the improvement rate may appear discontinuous, with periods of little improvement mixed with sudden noticeable gains.

Second, it recognized that the time-to-market is accelerating. The pace of new model releases has dramatically increased. Major capability upgrades that once took years now happen in months, with incremental improvements rolling out even faster through techniques like fine-tuning and prompt engineering.

Third is the rapid decrease in cost per unit of capability. This is particularly relevant for the widespread adoption of these platforms. What originally required expensive, specialized access is becoming broadly available, following a pattern similar to other computing technologies.

Finally, recent improvements increasingly span multiple modalities simultaneously. That is, text, image, audio, and code generation are advancing together rather than in isolation.

The overall pattern suggests we're in a period of exponential capability growth, particularly around practical deployment and cost efficiency. Many of these changes are invisible to consumers, as when a manufacturer can use AI to engineer robots that are used in all types of production to lower costs while reducing the frequency of warranty claims. In health care, we will see more robust disease diagnosis, faster drug discovery, personalized treatment plans, and robotic surgery, leading to longer and healthier lives and reduced healthcare costs. Little of that (except maybe lower costs) will be visible to us, other than, of course, in outcomes.

I’m not Pollyannaish about potential dangers ahead. The “AI 2027” scenario and others note the likelihood of social disruption, not unlike that initiated by the Industrial Revolution. However, there is no putting the Genie back in the bottle. It won’t all be good, but like other technologies, we have a track record of adjusting.

All I got out of this is: BEN’S moving to Portland!!!

Ben,

This is the future calling. Please send an AI plumber to fix my leaking toilet.

Jeff the Luddite.