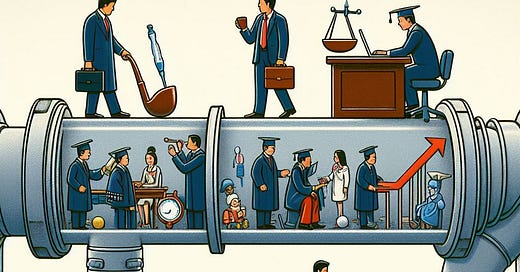

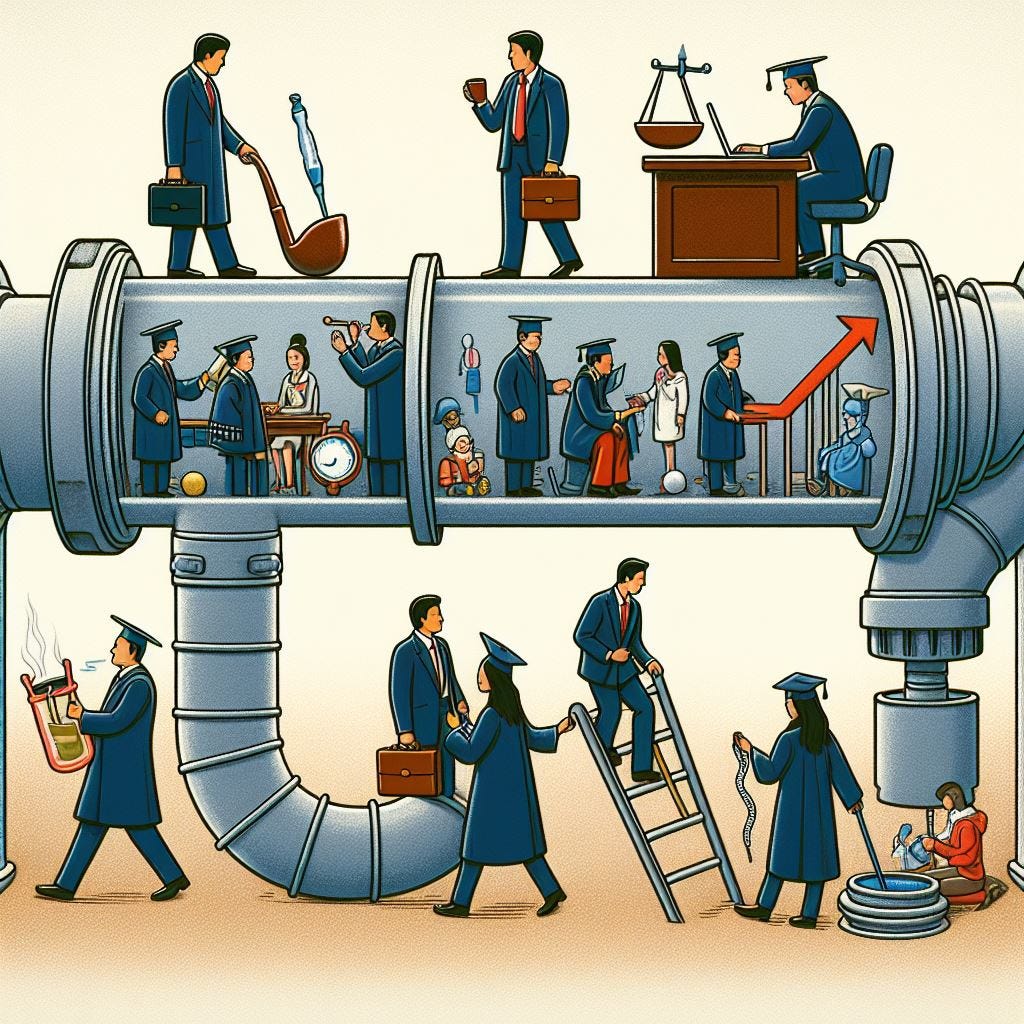

Breaking barriers and filling the pipeline

We usually reach the pinnacle of our professional achievement in our fifties and sixties. Racial and gender legal and socio-cultural barriers started falling in the 1960s. The pipeline is now filling.

Note: I want to welcome new subscribers who learned about the Pancake after a recent shout-out from Scott Van Voorhis at Contraian Boston. This is a must-read if you're a local or a Boston expat looking for a more complete view of the Boston regional landscape than the mainstream media provides.

Last Fall, I wrote about the challenge of determining pay bias by gender.

I observed then that we would expect those in almost any profession who want to attain greater responsibility and authority—not everyone does—to advance in that profession as they accumulate increased experience and skill and as they develop a broader network and earn a reputation.

Today, I want to follow up on this notion of “filling the pipeline.” We are regularly reminded of disparities in rank and compensation along gender and racial lines in areas such as chief executives and Board members of Fortune 500 companies, tenured faculty, public officials, and other areas where money or power are considered to be concentrated.

Starting with the empty pipeline

Sometimes, these reports explicitly blame some form of racial or gender discrimination for the gap with white men; in other cases, it is assumed that bias is the reason. It is incontrovertible that historically there were racial barriers as well as entrenched socio-cultural mores that explained the gross underrepresentation among racial minorities as well as women that impeded access to many occupations, let alone reaching their top level.

However, those barriers started to erode in the 1960s, picking up momentum in the 1970s and 1980s, often through legal remedies as well as a tsunami of social awakening, particularly in the area of women's opportunities. Those of us who lived through that period know that. We should all be reminded of those upheavals.

Whether we’re addressing gender or racial disparities in pay, position, or power, it's relevant to look at the forces and trends that will come into play in the future as well as where we are today. In short, I’m talking about how we are filling the pipeline.

It typically takes decades to reach the top

Executives, Board members, politicians, academics, researchers, and others usually reach their pinnacle of performance in their fifties and sixties.1 It takes years of experience and gradually increased responsibility, as well as achievement along the way, to become a top corporate executive, a university Provost or President, a high-profile Board member, a governor, senator, —or President.

These legal and socio-cultural changes only started showing up in numbers well into the 1980s, picking up momentum in the 1990s. And—with a lag—the results are only manifesting themselves in recent years—as would be expected. Consider some of the data that follows.

The average age of a Fortune 500 CEO is 58. That would be the age today for someone born in 1966. A women born that year might have graduated college in 1987. The percentage of women in the workforce in 1987 with college degrees, was only 23%. Today it is twice that. My class at Harvard Business School in 1969 was 2.5% women—about 17 out of 700. Today, it is about 42%.

When Ruth Bader Ginsburg enrolled at Harvard Law School in 1956, she was one of nine women in the class of 500. Indeed, in 1960 only three percent of lawyers were women. That almost tripled by 1980—but was still just eight percent. The next decade saw the percentage more than double and today is 39%. The class of 2025 at Hatvard Law School is 54 percent women.

In 1979, President Carter appointed 23 women to federal judgeships, which doubled the total number of women who served on the Federal bench in the previous 190 years. Today, women are one third of 1423 sitting federal judges, . The pipeline is still filling.

Major upheaval in medicine

Today, close to an equal number of men and women graduate from medical school. But it’s been less than 20 years since this parity was reached. In 1981, only 25% of medical graduates were women. The number has increased steadily since then, though it didn’t pass 40% until 1996.

Less and more dramatic in law

Most states do not track law school graduates by race or ethnicity. Although the total number of Black lawyers has increased substantially over the decades, if the goal would be to mirror the percentage of racial and ethnic groups in the population, there remains a negative gap. The U.S. Census estimated that there were 4,000 black lawyers in 1970; in 1980, about 15,700; in 1990, 24,700; in 2005, 44,800 and about 66,000 today, or about five percent of all lawyers.

Here again, the pipeline continues to fill; 7.8 percent of current law school students are Black, another 13.5 percent are Hispanic. The first African American federal judge took office in 1945. The first Hispanic federal judge took office in 1961.

The percentage of Black judges on the federal bench rose from 9.5% in 2020 to 11.5% as of Oct. 1, 2023. Overall, 163 federal judges identified as Black and another 10 identified as partially Black.

Meanwhile, 7.3% of federal judges in 2023 were Hispanic – up nearly one percentage point from 6.5% in 2020. Overall, 104 federal judges identified as Hispanic and another 11 identified as partially Hispanic.

Significantly, on the Federal bench at least, the proportion of Black and Hispanic judges substantially exceeds the percentage of those demographics who are lawyers.

Filling the government pipeline

The same forces that have resulted in greater participation in the judiciary can be seen at the highest levels of government and academia.

In the 100th Congress (1987-88) about 10 percent of the U.S. House of Representatives were women compared to none between 1973 and 1977. That grew to 29 percent women in 2023

The U.S. Senate included 25 women in 2023, compared to two women in the 100th Congress.

Among Cabinet-level positions, 11 in President Biden’s administration compared to a total of four during both of President Reagan’s terms.

In the 94th Congress (1974-75), 17 of the 435 districts (4 percent) elected a Black representative. Only one of 100 Senators was Black. In the current Congress, 27 percent of the House was represented by Black legislators. There were four Black Senators.

In 1964, there were only 70 elected black officials at all levels of government in the United States. Today [1980], there are over 4600….That power is perhaps most apparent in municipal government. Over 170 American cities, among them very large ones like Detroit and Los Angeles, have black mayors; in some of them, the passing of municipal power into black control appears likely to be long term….

In 2023, about 10 percent of all state legislators were Black, slightly under the proportion of the population). Almost a third of legislators in the states are women, more than six times the level of 1971.

Other indicators of change and accomplishment to come

In 1970, six percent of Black and six percent of Hispanic adults had completed a four-year university degree. Forty years later, that rate had tripled for Black adults and doubled for Hispanic adults.

Also, in 1970, in my era of graduate business school, only 4 percent were women. As seen in the table below, that proportion increased dramatically in the 1970s. For the MBA class of 2025, 42 percent are women.

The number of women in influential business positions is still low, but it’s a significant improvement from a few decades ago. The first woman to assume a CEO position in a Fortune 500 company was Katherine Graham, who headed the Washington Post in 1972—and assumed that position when her husband, Philip Graham, died suddenly. Since then, however, the number has been rising slowly to reach 37 in 2020 and jumped to an all-time high of 53 in 2023.

We see here how the pipeline has been filling up with the credentials that ultimately are needed for the top-level positions that determine policy, products, and power.

Should “equity” be determined by percentage of the population?

There is generally an assumption that “equity” is achieved if the proportion of participants in any role is proportionate to that demographic group's size. If it deviates too far, then often there is the implicit—or sometimes explicit—assumption that improper discrimination must be at work. If half of the population is women, then half of Fortune 500 CEOs should be expected to be women. If Blacks make up 13 percent of the population, then is something amiss if a lower percentage of university Presidents are Black?

That is a misguided metric on which to base policy. Discrimination, as a word, has developed a negative aura as it is often shorthand for racial, gender, ethnic, age, disability, and religious discrimination. Nevertheless, discrimination is important to employ—as in which political candidate would be better, which candidate for a job has the superior qualifications. As a teacher, I have to discriminate between an A+ paper and a B- paper.

Many occupations skew heavily toward one gender or race, leading to a workforce where 96.7 percent of preschool and kindergarten teachers are women, two-thirds of manicurists and pedicurists are Asian, and 92.4 percent of pilots and flight engineers are white. There are many reasons besides the illegal forms of discrimination why race or gender or other characteristics may vary. The players in the National Basketball Association are 73 percent Black men, but there is no assumption that white men, who make up about 75 percent of the male population, are being discriminated against. Why is there this racial imbalance? A topic of another time.

Only 10 percent of nurses are men. Again, we can spend some time exploring why that is so (and why it had increased from two percent in 1977) another day. The point here is that there is no concern that despite this imbalance between population and workforce proportion, there is an assumption that gender discrimination is at work among hiring managers.

Over the past 60 or 70 years, many barriers have come down that were, in reality, a function of discrimination, both legal in the form of Jim Crow laws in places and, with even greater impact, bias, and social norms. The former has largely been eliminated. The latter has gradually, though not totally, faded.

We need to accept that the basic building blocks for equity have been implemented. We see that in attendance and graduation rates in higher education, professional education, job opportunities, and policies such as affirmation action—whether required or morally adopted.

The pipeline takes time to fill. You know that when you attach a new 50-foot hose and turn on the spigot, the water does not pour out the end immediately. It takes a few seconds to fill before it flows. I see that phenomenon clearly in politics, business, and law—across the board. Nor should we expect that each generation and racial or ethnic group will want the same path. Equity should be valued in opportunity, not one-to-one outcomes.

Except in athletics and chess.

Good column. Pipelines are geographic too. The journalism field is a good example. In some regions and sectors, the diversity pipeline has been filled. In other regions and sectors, the pipeline is traditional with women and people of color merely tokens. Not only has the pipeline not been filled but it is closed with a big tight manhole cover.

Good points. I will admit that my observation is based on anecdotal data, not empirically based. No question that some school districts pay more now relative to the 1960s, but overall we underpay the people who pay a major role in providing the knowledge basis to be an informed and productive citizen Did you mean $5500 for the full year (probably $5000 for a non-masters degree teaching position)?