Is civil discourse dead? Was it ever alive?

"Jane you ignorant slut" was an SNL parody 50 years ago. Today, it could have come from our President. Are we doomed?

Civil discourse—the ability to discuss issues, disagree, and seek common ground—has long been a pillar of democratic societies. Yet, over the past several decades, many observers lament its decline. What has changed, and is this erosion, if indeed there has been any, as dire as it seems?1

First, there is the need to be sure we’re all thinking about the same concept. There is, wouldn’t you know it, an Institute of Civility. It notes that civility is more than just politeness.

It is about disagreeing without disrespect, seeking common ground as a starting point for dialogue about differences, understanding biases and personal preconceptions, and teaching others to do the same.

Traditional applications of civility that emphasize manners and behavior over meaningful engagement and shared understanding have led us to a fatal misunderstanding of how to resolve our differences. Forced politeness that conceals authentic human feeling only fosters resentment and drives agendas underground.

The flip side, of course, would be incivility, which encompasses rude, aggressive, condescending, and disrespectful behaviors. The Society for Human Resource Management (SHRM) has created a Civility Index by surveying 1,611 U.S. workers across industries about how often they experience or witness uncivil behavior in their daily lives and in the workplace. I grant that this leaves the notion of “civility” solely to the perception of each individual. With that caveat, the survey extrapolated that U.S. workers experience 202 million acts of incivility each day, with nearly 40% of the uncivil behavior happening at work. The SHRM calculates that this translates into roughly $2 billion per day in absenteeism and diminished productivity. For what it’s worth.

Certainly, any discussion of the loss of civility must start with the utter incivility of the shamer-in-chief. Though a cultural acceptance of incivility may have been well underway before Donald Trump rode down his escalator in 2015 and immediately dissed as a group all immigrants from the Global South, politicians he didn’t like as “losers,” while mocking an individual with a physical handicap, he has continued that pace of incivility both in tweets (or Xs) as well as from any podium he is behind. Even in his Oval Office. Donald Trump may have unleashed others with his example. As such, he may be considered an accelerant of incivility. But he didn’t start incivility, and it would exist even without him.

Is there less civility today than in the past?

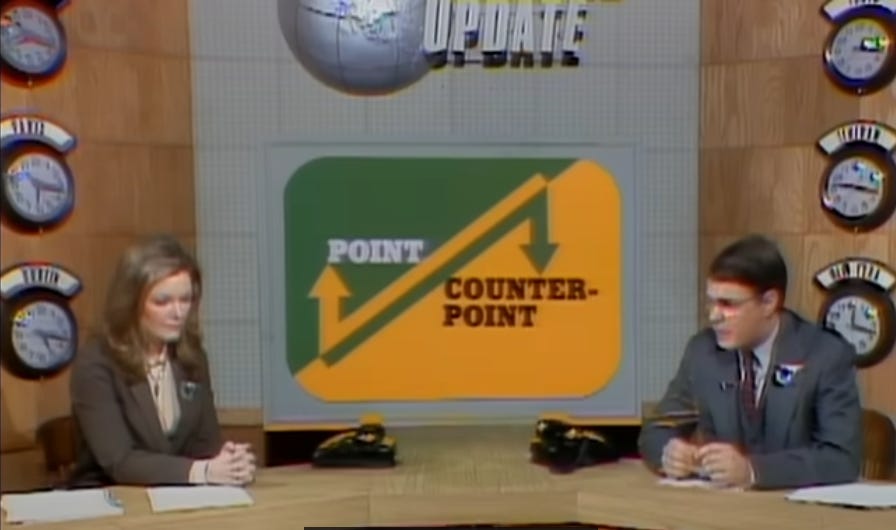

In the first iteration of Saturday Night Live, a segment introduced in 1978 on Weekend Update was “Point-Counterpoint.” It was patterned after a popular feature on the already well-established program “60 Minutes,” in which a “liberal, for a time, Shana Alexander, faced off against a conservative, James Kirkpatrick. This very civil exchange was fodder for the SNL parody, with Jane Curtin in the Alexander role, and Dan Aykroyd as the conservative. Unknowingly foreshadowing today’s confrontations, Aykroyd famously would start his rebutall with “Jane, you ignorant slut.” His “commentary” inevitably went downhill from there.

I wouldn’t be writing this if I didn’t think that there was an issue with civility and civil discourse. However, we really can’t say how recent it is. There are not many empirical measures of civility over time. One of the few data-driven studies parsed 1.3 million Tweets from members of Congress between 2009 and 2019 and found a 23% increase in incivility over that period.2 The study suggested that this rise was partly driven by reinforcement learning, where politicians engaged in greater incivility after receiving positive feedback (likes and retweets).

Our perceptions of past eras are largely shaped by the media, which are not likely to present an accurate—or at least complete—understanding of the discourse of the past eras.

In the popular British series, Downton Abbey, you may recall that one plot line involves a proposed government takeover of the local cottage hospital. Violet (the Dowager Countess) and Isobel Crawley have opposing positions. This becomes a significant point of contention between these two strong-willed women, who frequently disagree but maintain their friendship despite their opposing views.

Or consider the ongoing conflict between Tom Banson, the Irish socialist chauffeur, whose progressive views are anathema to the master of the house, Lord Grantham. They frequently disagree on politics, social equality, and the changing world, yet the discourse is quite civil, thank you. They even develop mutual respect despite fundamentally different worldviews.

On the other hand, I suspect we tend to overlook, perhaps willfully, the historic examples of incivility that we are exposed to via the media. Martin Scorsese's "Gangs of New York" shows incivility not merely as interpersonal rudeness but as outright violent tribalism, portraying the underlying ethnic and religious tensions that characterized parts of urban America in the mid-19th century,

An earlier Scorsese film, his adaptation of Edith Wharton's novel "The Age of Innocence," portrays a different form of incivility. Taking place at the same time as “Gangs of New York,” but within New York high society, Scorsese has described this as "the most violent film I ever made," via the emotional cruelty through subtle but devastating forms of ostracism and emotional repression. Social slights, deliberate exclusions, and ruined reputations become weapons wielded with surgical precision against those who violate unwritten social codes.

Political incivility can get physical

We needn’t depend just on fictional examples of the failure of civility in our past. For all the rancor in Congress today, none can—so far—compare with the physical violence among our elected representatives in the tense years leading up to the Civil War. Perhaps most well-known was when South Carolina Representative Preston Brooks brutally beat Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner with a cane in response to a fiery anti-slavery speech by Sumner. This act, which drew national outrage, symbolized the breakdown of civility and the rise of violence in the political arena.

Indeed, perhaps the ultimate endpoint of incivility is violence in response to speech. Joanne B. Freeman, a historian at Yale, identified at least 80 physical alterations by members of Congress in the three decades leading up to the Civil War. The Field of Blood. “Members of the House and Senate… brawled on the House floor; they faced off in duels; they fired shots in Congress. They beat each other senseless with canes.”

In 1842, Edward Black, a proslavery representative from Georgia, threatened to lynch an antislavery congressman, John Giddings of Ohio, for challenging the rule, then ran at him with a cane when he refused to stop. A year later, John Dawson, a proslavery Louisiana congressman, threatened to cut the throat of another gag rule-breaker, calling him “a d—d coward’ and a d—d blackguard.”

The women suffragettes in the early part of the twentieth century were accused of offending the manners of civilized society, and the predecessor of today’s bombastic radio talk shows, Father Charles Coughlin, used radio appearances in the 1930s to stoke anti-Semitism and inveigh against President Franklin Roosevelt as a socialist tyrant.

Compared to Civil War-era fisticuffs, South Carolina Congressman Joe Wilson’s shouting “you lie” during President Obama’s State of the Union address in 2009 was modest, though breaking with decorum. To his credit, Wilson apologized before the evening was out. “While I disagree with the President's statement, my comments were inappropriate and regrettable. I extend sincere apologies to the President for this lack of civility."

More recently, several Congressmen have shouted at the President during State of the Union addresses, disrupting the proceedings. Notable examples include Republican Representatives Marjorie Taylor Greene and Lauren Boebert, who heckled President Biden during his 2022 and 2024 addresses. Democrat Al Green was removed from the House chamber for shouting at President Trump during his 2025 address.

Why does it seem there is less civility?

So fierce disagreement is not new. We’ve seen a history replete with examples of heated debates, in the 19th-century U.S. Congress and likely many more unrecorded in taverns and living rooms. The difference today lies in the platforms and speed of communication, not necessarily the intensity of disagreement.

The perception of decline is partly nostalgia--past debates were often just as contentious, but the venues and language were different. Perhaps every generation perceives its state as being a regression from previous generations that they only know about second or third hand.

The role of social media

It should be no deep insight for you that we can lay much of the onus on the 21st-century spread of digital media in general and social media in particular. Indeed, social media seems to be the catch-all culprit for much of all good and bad changes in our culture. In the early 1990s, most Americans received news from a handful of major television networks, newspapers, and radio stations. This limited media landscape created shared reference points and common narratives that facilitated discussion across political divides.

Today's fragmented media environment allows us to consume information that confirms existing beliefs while avoiding contrary perspectives. Social media algorithms, designed to maximize engagement, tend to promote content that triggers strong emotional responses—often outrage or indignation. These platforms reward provocative statements over nuanced analysis, incentivizing performative conflict rather than good-faith dialogue.

The economics of incivility

Furthermore, the “attention economy” has fundamentally altered the incentives around public discourse. Thirty years ago, media outlets generally competed on reputation and perceived trustworthiness. While sensationalism certainly existed, there were stronger institutional guardrails.

Today, revenue models based on advertising clicks and engagement metrics have created perverse incentives. Conflict generates attention, and attention generates revenue. Fox News was at the forefront of discovering that opinion-based programming featuring partisan commentators drew larger audiences than straightforward news reporting. CNN and MSNBC have followed suit, to varying degrees. This business model has been amplified online, where outrage is among the most reliable drivers of engagement.

Political Polarization and Sorting

Dating back to at least 1961, when Newton Minow, President Kennedy’s chairman of the Federal Communications Commission, gave his “Vast Wasteland” speech, social commentary often derided the homogeneity of the mass media, television in particular. In a nutshell, the critique was that NBC, ABC, and CBS, the three national networks, were each motivated by economics to speak to as large an audience as possible, thus catering to the middle ground. As a result, the range of diversity was limited. As there were only three national news broadcasts, only 30 minutes each evening, all three covered the same items. Few cities had more than two newspapers. The closest approximation to public discourse was one or two local radio call-in talk programs.

However, in retrospect, we can see how this arrangement meant that vast swaths of America viewed the same news and entertainment. We shared a more common culture.

Falling in the category of “be careful what you wish for,” America today has such a proliferation of media outlets that almost any tiny niche of interest can be accessed. Podcasts, newsletters, YouTube channels, TikTok influencers, and all flavors of digital media have contributed to increasing political polarization, with fewer people occupying middle ground positions. Geographical and social sorting mean many Americans live in communities where they rarely encounter differing political views in their daily lives. Into the 1990s, there was substantial overlap between Democrats and Republicans on policy positions; today, the parties have moved further apart ideologically.

New York Times Publisher A.G. Sulzberger captured these trends in an interview last week:

We live in a moment of growing tribalism and polarization. Sadly, most media today make these divisions worse by telling each group what they want to hear. If you look at cable news or the podcast or newsletter ecosystems, that’s mostly what you’ll find. People parroting their group’s conventional wisdom or partisan talking points. Hyping convenient facts and downplaying inconvenient ones. And look, there is obviously a giant audience for all that.

When people rarely interact with those holding different views, it becomes easier to mischaracterize opposing positions and attribute malicious motives to the "other side." The human tendency toward tribalism—viewing politics as a team sport with clear winners and losers—has intensified as partisan identity has become more central to many people's self-concept.3

Discourse, of course, can be civil as well

For eight years, conservative Bret Stevens and liberal Gail Collins engaged in a weekly Point-Counterpoint-like text “conversation” in The New York Times. In their final entry last week, Stevens offered actionable advice for approaching potential contentious discourse:

I think it’s very important that you not go into a conversation with the idea that you’re going to win. It’s not a competition. It’s an effort to learn how the other side thinks. People have asked me, is persuasion possible? I have a hard time thinking it is. I think what you can do is make a person — a reasonable person — on the other side of an argument, say: “Hmm, I can see it. I can see what you’re saying.”

That doesn’t mean I need you to agree with me or that I need to kind of assert my intellectual dominance. It just means like, all right, I get it. That doesn’t sound completely stupid. And I’m going to go back and think a little bit about why that’s not entirely right or totally wrong. But the moment it becomes a competition, the moment pride gets involved, you’re doomed to bitterness.

I think it is one of the great perils of our democracy that people are losing the habits of a free mind, that they are so rarely exposed to a contrary point of view from a very early age, that they don’t enjoy the idea of mixing it up.

Stevens’ suggestion probably resonates with Pancake readers and is consistent with other reasonable prescriptions for individuals, such as to practice charitable interpretation of opposing views, seek diverse information sources, and prioritize relationships over political victories. Structurally, the collected wisdom calls for reconsidering the incentives built into our media and technology platforms, revitalizing community institutions, and creating more spaces for cross-partisan interaction.

Near-term remedy is unlikely

Civil discourse isn't merely about politeness; it's about maintaining the conditions that make democratic self-governance possible. Rebuilding it would be helpful, not just for social harmony, but for our continued ability to address complex societal challenges together. However, I’m not optimistic that this is realistic, certainly not with our current leadership. On the one hand, the skills required for productive disagreement—intellectual humility, active listening, and separating ideas from identity—can be cultivated. Any of us can work on that, and I suspect many of you have subconsciously, if not by design.

On the other hand, for the larger society, I see no current indications that could lead to a change. Yes, a useful start may be to recognize the forces that have eroded civil discourse over the past whatever number of decades, with the objective of effectively countering them, thereby creating a healthier democratic culture that acknowledges differences while maintaining mutual respect.

Oh, sure. And maybe we could teach cats to fetch our slippers.

Last week marked the 100th issue of The Two-Sided Pancake since I started publishing weekly on Substack in June 2023. That first issue had 19 views. In the last 30 days, the Pancake has had more than 2000 views, not including the Podcast. I just want to mark the occasion. Whether this is your first time here or you were among the 19 pioneers, thanks for the validation of the Pancake’s raison d’être.

Much of the research in this post is the product of requests to several large language model AI platforms I employ as my “research assistants." They include Perplexity, Claude, and Consensus. Often, when doing a Google search, the responses may include results from Gemini.

Of course, this may not be generalized to the broader population given its narrow range of subjects. We might also have issues with how incivility was defined. Still, it’s something and, intuitively, would seem to be consistent with expectations. Maybe even conservative.

Congratulations on your 100th Pancake. They have been a pleasure to read and think about. Most impressively, you've addressed a wide range of controversial issues with balance and depth. As to the current post, Jeff is surely right that social media has exacerbated the problem.

One of your best. When Tweeter arrived my immediate reaction was this isn’t going to be good for our society. Social media is such a destructive force.