Let’s talk artificial intelligence (AI)

The Luddites were wrong about industrialization. Will we survive AI job displacement?

As with almost any new technology, there are benefits and potential harms, sometimes unintended consequences. Alfred Nobel is credited with developing dynamite. An early use was in building and mining, with the expectation that it would reduce deaths in these hazardous occupations. We know how else it has been used. One of the early expected benefits of the internal combustion engine was that cars and trucks would reduce the pollution of all the manure, urine, and dead horses that had to be dealt with in the growing cities. Computers, too, brought predictions of benefits as well as warnings of negative outcomes. And we can go back to England and the introduction of power looms, resulting in the cost of cloth and clothing plummeting, but gave rise to the Luddites ready to torch factories that undercut jobs of home weavers. And home weaving is now only artisanal.

So AI predictions fit perfectly into the “there’s an upside, but what about the evil downside” model.

There’s no dearth of scenarios that range from “worrisome” to apocalyptic.

unemployment and social disruption: with AI applications taking over jobs from writers to accountants

Military applications and Cybersecurity threats: AI-powered weapons systems could be used to carry out autonomous attacks against human targets.

Bias and discrimination: AI systems are trained on data, which can reflect the biases of the people who collect and label that data

Loss of privacy: AI-powered surveillance systems could be used to track and monitor people without their consent

Misinformation: AI-powered propaganda systems could be used to spread misinformation and manipulate public opinion.

Superintelligence: Could AI eventually become so intelligent that it surpasses human intelligence? This raises the possibility that AI could become uncontrollable and pose a threat to humanity.

On the flip side of the pancake, AI has been attributed with the prospect of:

• Increased productivity and efficiency: AI can automate many repetitive and time-consuming tasks, freeing up humans to focus on more creative and strategic work.

• Improved decision-making: AI can analyze large amounts of data to identify patterns and trends that humans may miss. This can help make better decisions about everything from product development to medical diagnosis.

• Personalized experiences: AI can be used to tailor products, services, and recommendations to individual needs and preferences, resulting in a more satisfying and engaging experience for consumers.

• New and innovative products and services: For example, AI-powered self-driving cars are just one example already in development.

• Improved safety and security: AI can be used to detect fraud, identify potential threats, and predict natural disasters. This could help to make the world a safer and more secure place.1

So what are we supposed to do? Of course, focusing on the apocalyptic side immediately suggests a need for regulation. Fast. Sam Altman, the head of OpenAI, the company that developed ChatGPT, has indicated support for a proposal to create a federal regulatory commission to monitor AI developments.

My former colleague, Russ Neuman, is skeptical of such attempts at regulation:

Trying to regulate AI is like trying to nail Jell-O to the wall. It will never work. The attempt to direct this fast-changing category of mathematical tools through legislation or traditional regulatory mechanisms, no matter how well-intentioned, is unlikely to be successful and is much more likely to have negative unanticipated consequences, including delaying and misdirecting technical development. AI is the application of a set of mathematical algorithms, and you can’t regulate math.

Neuman adds that there exists “an extensive legal system for identifying and adjudicating such matters” (i.e., disinformation, identity theft, financial crimes) and that “attempts to outlaw potential behaviors before they take place is folly.” It would be akin to a regulatory agency for monitoring and controlling hammers and knives because they could be used in criminal activity.

Predicting is a hazardous occupation, especially when it deals with the future.2 In the early 1980s, when Apple II and Radio Shack TRS-80 personal computers first made their mark, there were all sorts of prognostications about how they would affect kids: they would become isolated, sitting alone at their screens, devoid of social contact. Yet when I went into a third-grade classroom in 1982 I saw students eagerly collaborating on a story that one student was entering on an Apple II’s green screen monitor. They didn’t do that kind of work before the PC.

Moreover, the Cassandras didn’t bake in networked computers 15 years later with the coming of the internet. Today “social media” is big and, if there are any complaints, it is that kids are too connected, too social in their posts and responses to one another.3

It would be folly for me to try to address the full panoply of AI issues. Let me pick out one that we can all relate to today: labor dislocation.

In the recent Writer’s Guild strike, the union wanted some strict limits on employing AI in creating scripts. That is probably reasonable in the short run, as a bridge to a day where AI applications may indeed churn out highly “professional” writing, indistinguishable from the work of the writers’ room. In the long term, most scriptwriters will not be needed, just as over the past 30 years the need for bank tellers has mostly atrophied.

Another industry that had a massive labor dislocation was newspaper production. Into the 1970s, most newspapers required large hot rooms filled with loud linotype machines, into which skilled operators keyboarded the copy of the reporters, creating type that was cast into lead that made up the columns that were eventually printed. In New York, the powerful International Typographers Union resisted the automation of this process. After a long strike at the New York Times, a contract allowed the Times to use the automated process—but they still had to keep the typographers on the payroll, setting duplicate type which was then melted down for the next day’s round of “bogus” type.

Yet over time, both the banking industry adjusted its hiring, while the typographers took buy-outs, retired, or just left and weren’t replaced.

One school of thought, voiced by Thomas Kochan, a professor at the MIT Sloan School of Management, like Sam Altman, proposes legislation as the answer, despite the unknown future.

The best bet for US workers might be legislation to set standards for corporate use of AI systems, Kochan said. For example, companies could be required to inform workers in advance about AI deployments, with detailed information about how the technology would be used. Kochan also suggested a law to require companies to set up employee advisory boards to give workers some say in how AI would be deployed.

The problem is, as Neuman so lucidly described it, AI is like Jell-O. It is a tool that is embedded in applications, much the same way that there is code in the WORD program I’m using to type this. Having to inform workers in advance of AI deployment would be akin to telling those typographers that computer code is being deployed in the applications being used to create type. Or informing bank tellers that computer code will be in the ATMs being installed. And what advice might “advisory boards” of the home weavers in 19th century England have volunteered? Maybe recommend the factory owners to refrain from installing power looms?

Most employment change is self-stabilizing. Take travel agents. In the 1980s there were about 46,000 travel agencies. Today, it is down to about 13,000. But the industry has also adapted. Today, those agents now go by titles such as advisors, consultants, counselors, and even designers.

Many accounting functions will take advantage of AI systems. Both creating and auditing financial statements are likely candidates for AI applications. As these changes move into societies and economies, fewer business school students will choose the accounting profession, just as earlier the automobile eliminated most jobs for shoeing and caring for horses or today’s computer-controlled automobiles have lessened the need for auto mechanics. What happened to all the typists in the old secretarial pools?

We’ve been down the route before, notes OpenAI’s Altman:

Pandaemonium (1660–1886): The Coming of the Machine as Seen by Contemporary Observers, is an assemblage of letters, diary entries, and other writings from people who grew up in a largely machineless world, and were bewildered to find themselves in one populated by steam engines, power looms, and cotton gins. They experienced a lot of the same emotions that people are experiencing now, Altman said, and they made a lot of bad predictions, especially those who fretted that human labor would soon be redundant. That era was difficult for many people, but also wondrous. And the human condition was undeniably improved by our passage through it.

So we need to take all projections with a modest dose of skepticism. One such stab compared AI’s eventual capabilities with the human abilities of specific professions ., such as written comprehension, deductive reasoning, fluency of ideas, and perceptual speed. It concluded that, unlike the skilled blue-collar jobs first clobbered by the Industrial Revolution, AI will come for highly educated, white-collar workers first. Lawyers, teachers, financial advisers, and real-estate brokers, among them. Ouch!

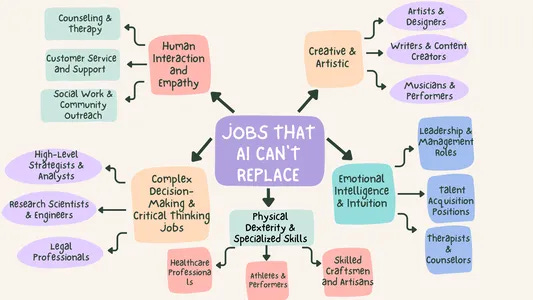

The above chart is one take on jobs that may be less susceptible to AI replacement. I don’t agree with all. In general, anything where a physical presence is needed is more likely to survive. We’re talking AI here—not robots, though those may proliferate as well.

There is reason to expect that the changes wrought by AI will descend on us faster than the generations over which the Industrial or Information Revolutions played out.4 And in the short term there may indeed be a need for some guardrails to cushion the transition, as the Writers Guild and Screen Actors Guild are seeking.

The jobs of the future are notoriously difficult to predict, and the Luddite fears of permanent mass unemployment never materialized. Instead, we replaced the 60-hour work week with the 40-hour week and an exponentially higher standard of living. If, in 40 or 50 years we can be more productive working 20 hours a week, maybe some short-term disruption could be tolerated and mitigated. Perhaps invest in the leisure time industry? We would need to do something with all those available hours.

I asked BARD, Google’s AI, to summarize the pluses and minuses of AI. Helpful.

I’ve heard this attributed to many different sources. It is likely derived from Danish physicist Niels Bohr, who said, “It is very difficult to predict — especially the future.”

Yes, there is also the argument that being screen social is different than being in-person social. But I don’t see evidence that we are getting together less with friends these days.

Is anything a “revolution” when it plays out over centuries or even decades?

Good job. I'm less optimistic than you that AI will be a neutral factor overall in employment status. But I agree that regulation/legislation will be difficult, at best, to achieve desirable social/economic objectives.

Very enlightening Ben. Thanks Sue