New Years Non-Predictions for 2025

Predicting is a hazardous occupation, especially when it deals with the future.

The beginning of a new year sparks numerous forecasts from many sources. While some may claim they possess foresight, others are merely offering educated guesses within their fields of expertise, including political commentary, legal analysis, business insights, or technological predictions.

Only in areas of scientific law can we predict the future with absolute certainty. I can predict without hesitation that sunrise in Boston tomorrow (January 7) will be 7:13 am.1 Beyond that, prediction becomes increasingly if-ier. Will the sun actually be visible at 7:13 in Boston on January 7? As I write this, the folks who predict the weather give it a high probability but under 100%.

Will Donald Trump be inaugurated at noon (EST) on January 20? Highly likely. However, you could imagine scenarios, both man-made and natural, that could prevent that, so we might want to give it a 99% probability. But during his term will he fulfill one of his campaign promises, to eliminate birthright citizenship? I dunno. Maybe an 80% likelihood he will try. Do you want to predict the probability of him succeeding?

The best predictions are based on an extensive analysis of past events and the forces and trends at play in the area of the intended forecast. Experts might be expected to be more successful than more pedestrian analysis, though that might be a fatal assumption. For example, the seven sports columnists for the Boston Globe predict the likely winner of every football game each week. These are aficionados who make following sports their livelihood. For the current season before last weekend’s games, the best of them predicted the winner (against the point spread) only 56% of the time. The lowest barely edged out chance, 51%.

The path to the most successful prediction is straight through extreme generalization. Astrology is a pseudoscience that reeks of big-picture predictions.

Ophira Edut is the co-author of 22 books. She is one of the go-to astrologers for yearly predictions and has reportedly done readings for the likes of Beyoncé, Alicia Keys, and Dua Lipa. Her “predictions for 2025:”

And she says to get ready for major innovation in technology (AI is here to stay...and just getting started) as well as big developments in spirituality and mysticism to balance it out. Relationships, especially romantic ones, are going through a growth phase, and we may see both ultra-traditional and wildly non-traditional new arrangements in how people share space, co-parent and design their love lives. By the end of the year, life on this planet could look very different (think: flying cars).

So there’s some action you can bank on.

Picking on astrology prediction is low-hanging fruit. So, let’s hone in on some serious predictions. U.S. News & World Report attracted me with the headline, “New Year’s Predictions: What to Watch Around the World in 2025.” Their columnist sought out the experts at the Council of Foreign Relations. Typical of their combined wisdom:

The Middle East seems poised to dominate headlines. Will post-Assad Syria unify disparate opposition groups? Or will it remain a failed state, only this time, run by Islamists? Syria’s fate will not only define the future for the country’s 23 million people but also have a significant impact on its immediate neighbors: Turkey, Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon and Israel.

The return of Trump cuts both ways for Taiwan. On one hand, the president-elect has promised to sharpen U.S. competition with Beijing. On the other, he seems to harbor no affinity for the democratic island and has criticized its success in becoming a semiconductor powerhouse at the expense, in his view, of the United States. President Joe Biden has mused about coming to the defense of Taiwan in the context of a Chinese invasion; Trump has suggested he might slap tariffs on China instead.

Maybe it was just a bad headline.

Perhaps the “12 Tech Predictions For 2025 That Will Shape Our Future,” compiled by the smart journalists at Forbes, will help me see the future.

Advancements in technology will shape economic growth. There will be an apparent dichotomy between countries that participate in the innovative economy and those that lack the ability or infrastructure to do so. …Those failing to do so will lag behind, while others, such as the BRICS group, will continue to seek a shift from the U.S. dollar.

Crystal ball gazing or navel-gazing? Hmmm—those who succeed will be successful. Those who don’t will fail.

While some predictions may be more for entertainment than for influencing actions, others carry higher stakes. For gamblers, predicting the total of the next roll of the dice is pure chance. But predicting the winner of the next horse race can involve at least a patina of analysis of past performance of the animal and its rider, the condition of the track, and so on. Investors will study macroeconomic trends (expected interest rates, money supply, inflation expectations) as well as the trends in a particular industry (e.g., new car sales), and finally, the products, management, and financial condition of a particular firm before venturing a predication over that company’s prospects and suitability for investment,

The stakes are high, so the accuracy in predicting the financial future is a popular end-of-year activity. Underestimating the expected strength of the economy can result in conservative investments, thus leaving money on the table should the markets perform better than predicted. On the other hand, a plan based on an overly optimistic financial future could lead to strategies using leverage (debt) and, therefore, substantial losses should markets underperform.

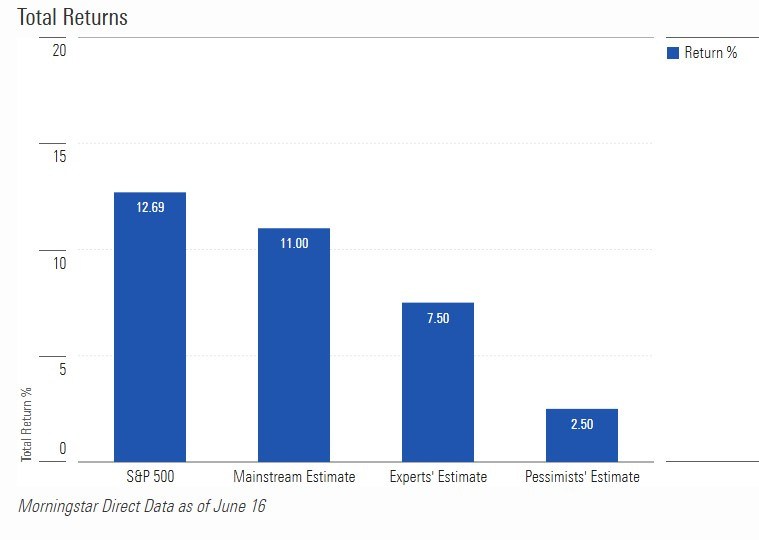

The chart below aggregates a range of predictions for the S&P 500 index over the 10 years from mid-2014 to last year. Significantly, the crowd-sourced prediction of everyday investors was vastly superior to the forecast of “experts, “ particularly the Pessimists.

Predictions and Performance of S&P 500, 2014-2014

Megamistakes

A prediction may be spot on and still miss the mark. Is that a contradiction? My favorite example I’ve cited over the years came from a market research firm in the early 1980s that was selling its prognostications to all those interested in the nascent market for home video. In 1982, the video cassette recorder (VCR) was still a novel device. Just as manufacturers, led by Sony and Matsushita, were gearing up production, there was also interest in a competing technology, the video disk player (VDP). Sony had a pony in that race, as did RCA, with vastly different technologies.

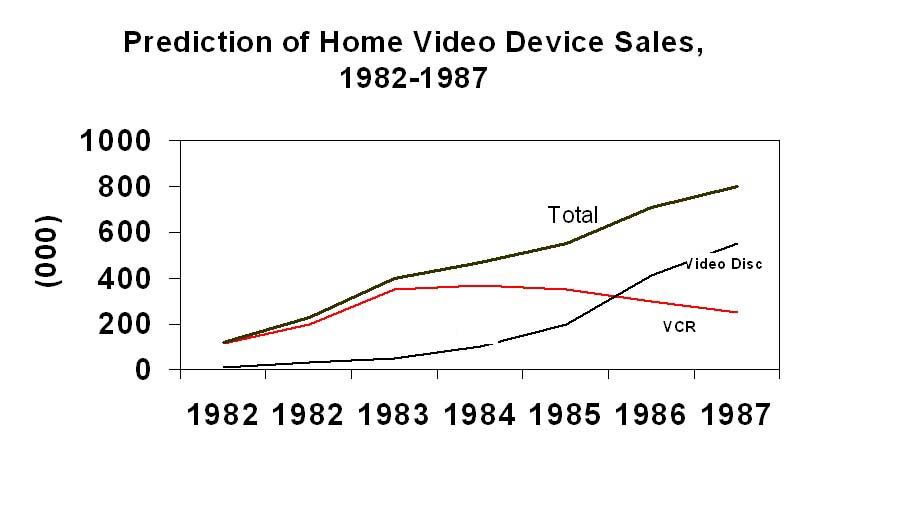

Enter Predicasts, the market researchers who examined the pros and cons of the two technologies capable of playing videos at home on the television set. Based on their analysis, Predicasts projected the total expected sales of home video devices, broken down by VCRs and VDPs. I haven’t tracked down the original graph, but it looked like the one recreated below.

The actual number of devices sold in 1987 was remarkably close to the prediction of five years earlier. The discrepancy was that it had the sales of VCRs and VDPs reversed. The analysts thought the discs (which back then were the size of LP records) would be easier to use and the players less expensive to make and thus sell. What they neglected to account for—or weigh heavily enough—was that consumers were reticent to buy VDP when little content was available on disc. And those who had the content—like the movie studios—had little motivation to license their libraries given so few households with VDP. A typical chicken and egg dilemma.

On the other hand, VCRs could record off the air programs for consumers to watch later. Consumers thus created their own content. That “primed the pump” for a large enough installed base for content providers to put their movies and other content on tapes, which gave rise to Blockbuster and the rental market. By the end of the decade, the original VDPs were destined for exhibition at the Smithsonian. Of course, in the 1990s, the DVD, far more compact and of greater quality, came along. With the vast network of tape rental stores in place, there was a built-in infrastructure for distributing DVDs, thus ending the reign of the VCR. Nonetheless, if you bought into the Predicat forecast in 1982 and thought RCA would be a profitable investment thanks to its early video disc player you would not have done well.

Predictions of technologies vie with business and financial forecasts for the most fertile soil for prognosticators. One of my favorite studies of all time is Megamistakes: Forecasting and the Myth of Rapid Technological Change. Author Steven Schnaars parses hundreds of predictions and breaks down the factors for their falling short and occassional success for many of them. Those that tend to be largely accurate seem to be so either by happenstance or the law of large numbers—predict enough, and by chance, some will seem prescient. Even a stopped clock is right twice a day.

Early on, Schnaars offers a list of predictions made by Herman Kahn, a founder of the Hudson Institute who had a reputation as a futurist by the 1960s. In 1967, he and colleagues published 100 technical innovations that were “very likely” to come to fruition by 2000.

Few of the predictions were accurate. Among those that were outright and clearcut misses were “Human hibernation for relatively extensive periods (months to years.” “Improved capability to “change” sex of children or adults.” “Generally acceptable and competitive synthetic foods and beverages.” And “Permanent inhabited underseas installations and colonies.”

Only about 15% of the forecasts were clearly correct, as calculated by Schnaars. Kahn correctly foresaw the widespread adoption of pocket-size televisions (I bought my father a Sony in about 1984), the VCR, and personal pagers. He unambiguously predicted the substantial influence of computers in business, professional, and personal use. He was accurate in his expectations for satellite communication and high-altitude photography for geological surveys. Some on the list, such as video conferencing and space defense systems, have become reality, but decades after Kahn’s time horizon.

How the sausage gets made

Predictions come in all shapes, sizes, and formats. Astrologers may employ the mumbo-jumbo of their charts. More serious prognosticators (sorry, astrologers) may combine what they consider macro factors—such as the national or even global economy, demographics, and technical and scientific work in progress—with ground-level detail and highly local observations, such as management changes at specific companies, weather balloon data for meteorologists, and Stage 3 clinical reports on specific drugs.

The data may then be run through the brain of an individual or small team with various levels of knowledge and wisdom for a “best guess” or fed into some rules-based model in a computer-run algorithm that massages it all and spits out its “best guess.” I’ve been in the former encampment with predictions and scenarios in technology and politics.2 (Most recently, see—or avoid— my “prediction” that Trump wouldn’t win the 2024 election.) A weather forecast may be the quintessential example of the latter form of prediction we are familiar with.

Another approach that has become available with the internet is some flavor of crowdsourcing. This is obtaining information or input into a task or project by enlisting the services of many people, whether expert or not. In the above chart, “Predictions and Performance of S&P 500,” the “mainstream” predictors would have come from crowdsourcing. And the result may be relatively accurate. Political polling is a purposive form of crowdsourcing. In the last Presidential election, most of the polls were quite accurate in predicting a very close popular vote within their stated margin of error.

A modification of crowdsourcing is the Delphi Method. A group of experts is recruited. Several rounds of questionnaires are sent to the group, and their anonymous responses are aggregated and shared with the group after each round. The experts are asked to adjust their answers in subsequent rounds based on how they interpret the “group response” that has been provided to them. The Delphi method seeks to reach the correct response through consensus. I participated in one in 1996, looking out to 2007. that tried to forecast the telecommunications industry. In retrospect, it got much right, but many sectors were off (e.g., predicting cellular providers would be in competition with “PCS entities,” whatever those were.)

At least three factors make most predictions unpredictable—certainly, those that extend beyond the very short term: social behavior, linear projections, and Black Swans.

First, social behavior is too variable. Social mores change. For example, in the late 1960s, the liquor industry expected that as baby boomers reached the drinking age, Scotch sales would benefit big time. After all, Scotch had been the whiskey of choice for their parents’ generation. Nope. Instead, lighter spirits such as vodka and tequila dominated.

This highlights a second factor: the strong tendency to project trends linerally. Sometimes, trends continue for a time—but not universally. In making his predictions, Kahn believed we lived in a rapidly changing world, that “present rates of innovation will continue,” and that the rate of change “is the only basis for predictions.”

No. It may be one basis for prediction. As already noted, social behavior can change. They are, in turn, affected by a third counter-prediction factor, so-called Black Swans. These are the unexpected, rare, and unpredictable events that defy our usual expectations and profoundly impact our world. We might also see these as the Unk-Unks—the unknown unknowns.3 For example, the space race to the moon that drove much technical innovation of the 1960s was upended by an energy crisis (long lines at gasoline stations and rapid price increases, if you were around then) in the 1970s due to geopolitical upheavals in the Middle East. We can’t plan around events we didn’t even know enough to build into our assumptions, like the COVID-19 pandemic we just endured.

So, I will refrain from making my list of predictions for 2025 or beyond—except for one: many of the predictions you may have seen in recent weeks will not come to pass. At least, that’s what my horoscope tells me.

Even if some apocalypse destroyed Earth beforehand, the sun would appear where Boston was at that time.

However, I predict that recent advances in AI will dramatically improve the quality of many types of forecasting based on large language models rather than lists of rules.

I first heard this term in the early 1980s from my colleague, Tony Oettinger, then chairman of the Program on Information Policy at Harvard. Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld popularized it.

I didn't attribute my version because I haven't found authenticatation. I had heard it attributed to Casey Stengel, another Yankee. So maybe that says something.

Given my grandson's child care is closed this week due to Covid-19 infections I'd say we are still enduring the infections. Damn.