The Pete Rose Hall of Fame Debate: Should He Be Admitted?

Should one's character be a qualifier for judging one's professional accomplishments? Should we award a Nobel Prize in Anything to a philanderer? The Philosopher is in.

You needn’t be a baseball fan for this Pancake. This is a story of classic tragedy and morality. It’s not about baseball.

Should Pete Rose, the baseball great who died September 30, be admitted to the Hall of Fame? His sin, of course, was that he was found to be betting on sports and, most significantly, baseball while he was active. According to the investigative report commissioned by Major League Baseball, he wagered on his own team, though, for what it’s worth, only for it to win. As a result, he accepted a ban on his being a player, manager, or executive. And later, a rule promulgated by the Hall of Fame meant that he could not be voted into that distinguished fraternity.

So dig in for a moral conundrum.

1. The context

Pete Rose’s major league career spanned 24 years as an active player, from 1963 to 1986, continuing for three more years as the Cincinnati Red’s manager. In August 1989, he accepted a determination that he was being placed on baseball's ineligible list for betting on baseball games, including his on own team:

Rule 21 Misconduct, (d) Betting on Ball Games, Any player, umpire, or club, or league official, or employee, who shall bet any sum whatsoever upon any baseball game in connection with which the bettor has a duty to perform shall be declared permanently ineligible.

In addition to the ban from baseball, in 1991, in a move aimed squarely at Rose, the Hall of Fame excluded individuals on the permanently ineligible list from being inducted by the Baseball Writers' Association of America (BBWAA). This is the organization that votes for Hall of Fame players during their 15 years of initial eligibility. After that expired, and Rose would have been eligible to be considered by the Veterans Committee (now called the Era Committee), another change was made that specifically barred players and managers on the ineligible list from consideration.

This was on top of the so-called “character clause” in the BBWAA’s election rules that specifies:

Voting shall be based upon the player's record, playing ability, integrity, sportsmanship, character, and contributions to the team(s) on which the player played. [italics added]

2. Argument For Admitting Pete Rose

The narrative for Rose’s Hall recognition largely starts and ends with his unmatched career achievements on the field. Pete Rose holds the record for the most hits in MLB history with 4,256 hits. That surpassed the long-time record holder, Ty Cobb, by 67 hits. To put this achievement in perspective, Hank Aaron, third on the all-time list, had “only” 3771 hits. Among currently active players, the LA Dodgers 34-year-old Freddie Freeman has 2267 hits and would need five highly productive seasons just to reach the 3000 hits of Roberto Clemente—number 33 on the list.1

Rose’s career batting average was .303. Among active players with at least 1000 at-bats, Houston’s Jose Altuve has the top average, at .306. The aforementioned Freddie Freeman is second at .300. Three times (1968, 1969, 1973) Rose was the batting champion in the National League.

Over his career, Rose earned an MVP designation and was selected to the All-Star team 17 times. These accomplishments alone make a strong case for his inclusion based on merit.

On the other hand…

3. Arguments Against Admitting Pete Rose

Most obviously and blatantly is Rose’s violation of baseball’s cardinal rule. Betting on baseball is considered one of the most serious offenses in the sport. Rose’s actions violated MLB’s Rule 21, which mandates permanent ineligibility for anyone involved in betting on games. This rule is considered fundamental to maintaining the integrity of the sport.

Moreover was his lack of remorse and continued gambling. Critics point out that Rose initially denied the allegations and only admitted to betting on baseball years later. Additionally, his continued involvement in gambling activities has raised concerns about his commitment to upholding the integrity of the game.

Finally, there is the argument that allowing Rose into the Hall of Fame could set a dangerous precedent, potentially undermining the seriousness of gambling violations. It could send a message that exceptional talent can excuse unethical behavior, which might harm the sport’s reputation. As I explain below, however, that train long ago left the station.

The moral question

This, then, brings us to the larger question of whether it is morally reasonable to separate on-field performance and off-field actions. Or more generally. professional accomplishment from personal failings. I recognize that this is a deeply personal question. I’m neither a philosopher or a moralist (though I may play on on the Pancake). I have my point of view and have engaged with others who make a strong case for an opposing conclusion.

In the specific case of Pete Rose, as far as has been determined, his betting activities occurred after his playing career, though he was still the manager of the Reds. Should the betting overshadow his on-field achievements? Should the Hall honor players for their contributions to the game rather than their personal conduct? In 2022, former Baseball Commission Fay Vincent2 proposed that “the Hall of Fame should revise the election rules to eliminate the hopelessly vague character standard.” Although he was advocating for admitting the steroids-addled players his argument would apply to Rose as well:

The Hall of Fame’s job is to look backward and honor past performance. Major League Baseball tries to protect the future of the sport by defending its integrity. By trying to inject nobility into its election standards, the Hall of Fame aimed to maintain the old-fashioned view that honors should accrue to the honorable. Messrs. Bonds and Clemens may not have been saints, but they were great players. Pretending anything else matters is hypocrisy.

There is the precedent of forgiveness or forbearance

The Hall of Fame has inducted players with, to put it gently, controversial pasts. Robert W. Cohen’s book, Baseball Hall of Fame — or Hall of Shame?, catalogs reprehensible acts of some Hall of Fame inductees.

is without question the Hall of Famer mentioned most often whenever the integrity of the game’s top players is questioned. Known as the Georgia Peach, he was often painted a racist and had numerous documented altercations with African-Americans off the field, including one that led to a charge of attempted murder.

Cobb, along with his fellow Hall of Famer Tris Speaker, was also implicated in a game-fixing scheme. Several researchers have written that Cobb and Speaker were members of the Ku Klux Klan, although that has never been conclusively verified.

“In theory, when it comes to these kinds of votes, it’s true that character should matter, but once you’ve already let in Ty Cobb, how can you exclude anyone else?” asks Cohen.

Moreover, Cobb is in good—or infamous—company. The Chicago Cubs Cap Anson helped make sure baseball’s color line was established in the 1880s and refused to take the field if the opposing roster included black players. Anson was enshrined in the Hall of Fame the year it opened in Cooperstown, N.Y., in 1939.

Chicago White Sox owner Charles Comiskey, class of 1939, “outed” the African-American infielder Charlie Grant, who was posing as a Cherokee. Kenesaw Mountain Landis (1944), the baseball commission for three decades, was an architect of baseball’s segregationist policy.

They were among those who became Hall of Famers before the inclusion of the character clause, though I’ve uncovered no movement to delist them, nor others of a similar pedigree. Meanwhile, many inductees have been elected post-character clause. Pitcher Gaylord Perry (class of 1991) doctored baseballs with spit, Vaseline, and other substances to confound hitters, clearly disregarding the rules. “All of baseball knew what Perry was doing even if he never admitted it — until writing a tell-all book after his retirement, wrote Cohen. And then there is Orlando Cepeda, who served 10 months in prison for smuggling marijuana in Puerto Rico. The Era (Veterans) Committee seemed to think this didn’t impugn his character, and Cepada was given the Golden Ticket for the Hall in 1999.

There are quite a few others who made the Hall despite serious questions that could be raised about their life outside of baseball: Roger Hornsby (racetrack gambling), Paul Molitor (drug use), Wade Boggs (extramarital affair), Duke Snider (cheating on income taxes), among them.

Like Rose, however, none of these transgressions had anything to do with the qualities on the ball field. These are very different from the players who, for the most part, had stellar careers but have been shunned by the Hall due to steroid use, Mark McGwire, Barry Bonds, Roger Clemens, and Sammy Sosa, among them. They may have had outstanding careers sans the enhancements, but presumably, some portion of their success in baseball was due to the illegal pharmaceuticals they inbibed. Unlike Fay Vincent, I see these as a very different case than Rose and other’s Cohen calls out.

But there’s a real distinction between a player who does inappropriate things not related to his job and a player who does inappropriate things that affect his job,” said Bill James, an influential and pioneering baseball author and statistician who wrote the book “Whatever Happened to the Hall of Fame?

I agree.

By the way, the Hall seems to want it a bit both ways. While they have blackballed Rose as a player, the museum has the bats he used for his 3,000th and 4,000th hits, the helmet he wore when he topped Ty Cobb’s hits record, and a Montreal Expos cap Rose wore when he set the record for games played.

Conclusion

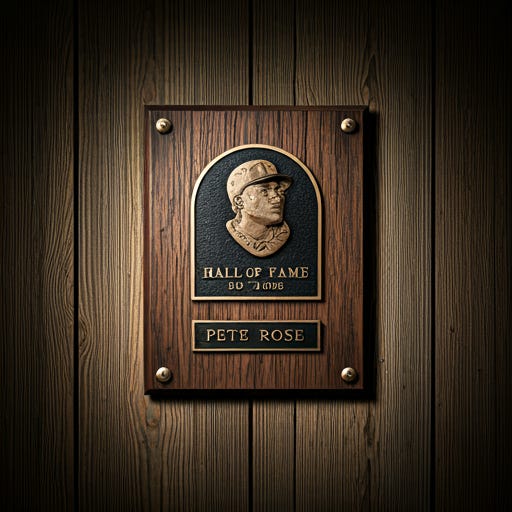

What is the Hall of Fame’s purpose? I advocate that the Hall should primarily recognize on-field achievements, and Rose's accomplishments are undeniable. Off-field behavior should not be a disqualifying factor. It would certainly be appropriate for his plaque to note his betting and subsequent ban.

The debate over Pete Rose’s Hall of Fame eligibility is complex, balancing his extraordinary career achievements against the gravity of his misconduct. Whether or not he should be admitted remains a contentious issue, reflecting broader questions about ethics, forgiveness, and the values that the Hall of Fame represents.

Indeed, as I started listing the pros and cons of whether the Hall of Fame exclusion should be reversed, I recognized that there are the larger ethical and moral questions of whether one’s achievements or accomplishments can be cleaved off from one’s personal life. In other words, could, for example, the Nobel Prize for Medicine be awarded to an otherwise worthy recipient who was also known for spousal abuse or who has been arrested for multiple DUIs?

What do you think? Should Pete Rose be admitted to the Hall of Fame? Or comment on the cosmic question of whether there is a meaningful distinction between one’s personal life and professional accomplishment. Share your thoughts in the comments below!

At his peak, Rose was connecting with about 200 hits per season. A really good year for today’s leaders, such as Freeman or the Phillies’ Trea Turner, might be 170 hits. One contributing factor to the likely future security of Rose’s record is that pitchers have upped their skill level—throwing harder and doing more tricks with the ball—than in Rose’s era.

In 1992, Rose petitioned the Commissioner—Fay Vincent—for consideration to be reinstated. Vincent never acted on the request.

I also agree with Bill James, but I don't agree with your interpretation of his premise. How can you conclude that what Rose did was not related to his job? As the manager of the Reds, his actions violated a fundamental rule designed to protect the integrity of baseball. To ignore these actions and enshrine him in the Hall of Fame would mean that rules don't matter. However, I would be OK if Rose was inducted into the "Hall of InFame" along with McGuire, Sosa, Bonds, and Clemens.

I don't see the value in glorifying his accomplishments when it requires purposely ignoring his transgressions. That's not a good look for the Hall of Fame. Consider the whole person and proceed accordingly. Not sure if this rule applies to the Nobel ...