What do you know about price discrimination?

Is it equitable that you and I are charged different amounts for the same thing? And will AI make things better or worse? No surprise for the Pancake community: it depends.

There is widespread interest these days in equity. So is it equitable when you and I are charged different prices for the same product? I hope you didn’t say “no,” because if you did you’re going to be upset by what follows.

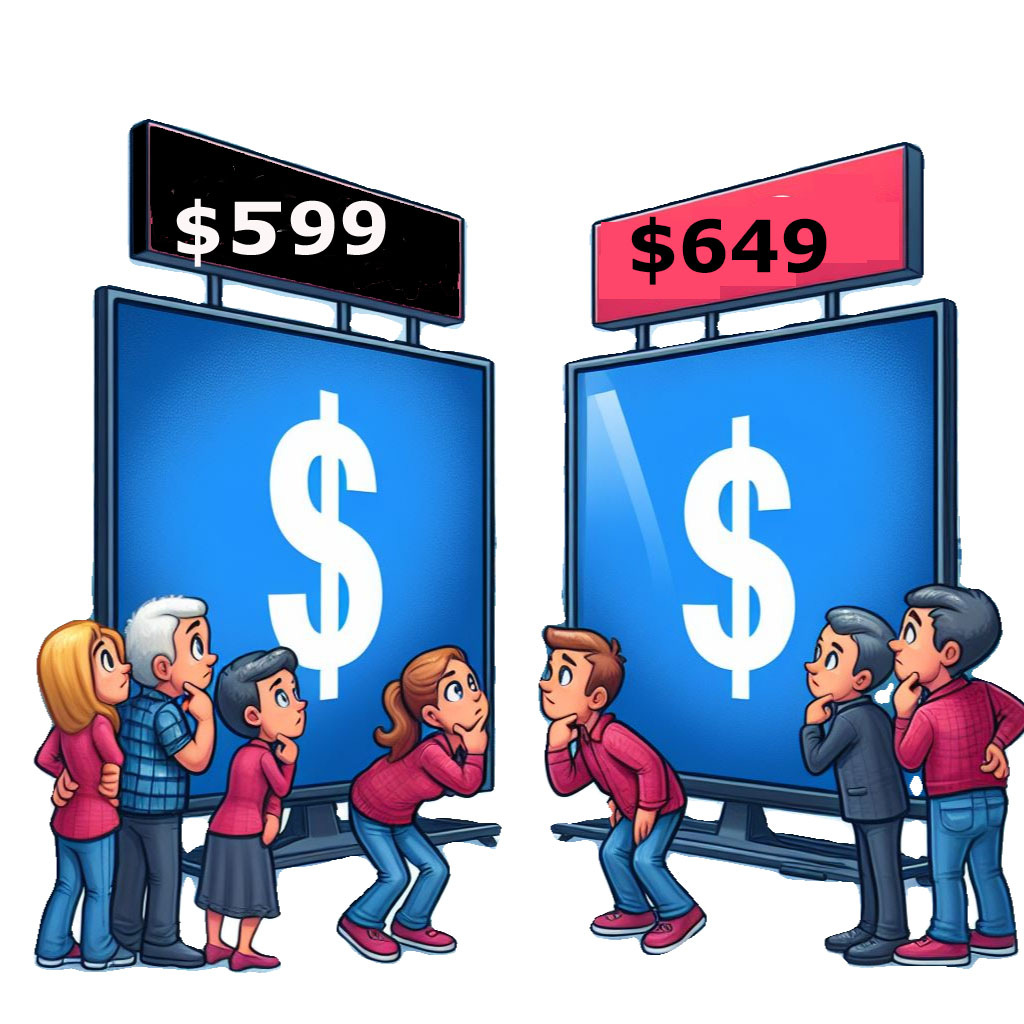

You’re probably aware that when you are on a flight from here to there that the passenger across the aisle is very likely to have paid a different price for that seat. It could be lower or substantially higher than yours. And yet you will both arrive at the destination at the same time, sitting in comparable seats and provided the same services (e.g., a beverage and maybe a snack). Economists call this price discrimination.1

There is nothing new about the concept, but computers and algorithms have made it more readily employed, more efficiently, and more broadly. It is one way many businesses can maintain profits, while consumers can benefit from lower costs or, in some cases, enjoy greater availability when a product or service is most needed.

I bring this up because, thanks to the development of artificial intelligence programs, we will be seeing more examples of price discrimination and related implementation of dynamic pricing—where prices can be changed as conditions, demand, and supply change. Get used to it. And, hopefully, understand that while sometimes dynamic pricing may result in you paying more than your neighbor, other times you could be paying less. It can also be used to change behavior.

A few examples

Hand sanitizer. When the COVID pandemic hit, there was suddenly an exponential increase in the demand for hand sanitizer. A product that had been a sleepy commodity suddenly was in demand far in excess of inventory or in the capacity of manufacturers to quickly increase the supply. What happened? It was usually out of stock at CVS, Walgreens, and most anyplace that typically stocked hand sanitizer. When a small shipment would arrive, it was swiftly scooped up by the lucky customers who found a few bottles. So some merchants raised their prices to take advantage of the demand/supply nonequilibrium. They were often accused of price gouging. Or were they actually allocating the supply to those who had the greatest need?

Last June I reposted a piece here, “Is it price gouging or market efficiency?” It describes a very crude form of dynamic pricing. You should read it. But since you probably won’t, here’s the abridged version: A convenience store receives a small supply of hand sanitizer. If it sold them for the usual $4, they’d likely be scooped up quickly—perhaps by hoarders. Anyone who arrived at the store soon thereafter would find the shelf bare. But what if the shopkeeper raised the price to $15?2 Customers who just wanted to “stock up” would pass. One customer, call her Justine, is indignant when she sees the price and posts on social media that the store is price gouging. But here’s a scenario if priced at $15.

Jeffery enters 10 minutes later, is surprised that the sanitizer is in stock, but figures for $15 he can live without. Audrey, then Margie, also decide that it’s not worth $15…. So the only reason why there is even hand sanitizer by the time Justine arrives is because of the $15—the price gouging—kept it there.

This also means that the store has not made any sales of sanitizer. But shortly after Justine leaves, Don, the owner of a small restaurant that is trying to survive on take-out and delivery, comes in desperate for hand sanitizer. He promised his new delivery man sanitizer, which has been nowhere to be found….The $15 price is high, but this is important to his business. He buys three bottles.

The next morning, Janice is the first customer. She finds there is sanitizer that she also very much needs. She runs a daycare for the children of the medical workers at the nearby hospital…. But her regular supplier says there will be no more this week. She, too, is surprised at the $15 price, but she is elated to find the product at all. She takes the remaining three.

Certainly, this wouldn’t benefit everyone. Perhaps a home health worker earning $12/hour needed the sanitizer and for whom paying $15 would have been onerous. But if it had been priced at $4 it probably wouldn’t have been on the shelf anyway.

Car services. The car services like Uber and Lyft built in a form of price discrimination from the start, which they called “surge pricing.” They employ their algorithms to monitor the demand for drivers compared to the number of drivers around at any given moment. If demand suddenly jumped—say, when a concert ended—then by offering drivers higher payment they could dynamically entice more to become available, while at the same time discouraging some number of concertgoers from foregoing a ride in favor of walking, taking public transportation, or sharing a car with a friend going the same direction.

Surge pricing would also make it more likely that a customer who needed a car quickly—maybe for a trip to the hospital—would be relieved one was available, even if the price was higher than usual. Taxis, which must charge the same price no matter what the demand, may hard to find at peak times.

Fast food. Some restaurants have started adjusting prices depending on the time of day or week. In February, Wendy’s announced that it would implement dynamic pricing, lowering prices during slack demand times. The backlash was delayed but then fierce.

On X, Senator Elizabeth Warren called the plan “price gouging plain and simple.” Burger King trolled Wendy’s: “We don’t believe in charging people more when they’re hungry.”… The anti-Wendy’s backlash made sense. Who wants to pull into a drive-through without knowing how much the food is going to cost?

There are many other examples of price discrimination that we don’t think about because it is so much a piece of the fabric of our routines. Have you ever put an item in your online shopping cart, but not completed the sale? The next day you may get an email offering you a discount code to complete the purchase. So maybe I bought it at full price and you get the same item for less.

We sometimes hear that prices in low-income communities are higher than elsewhere. But it could be the reverse. Many years ago—long before computers— I was shopping for a movie projector (that alone indicates how long ago). I was at a Sears in a working-class section of Philadelphia and saw the projector I wanted, but didn’t buy it. A week or two later I was at a Sears store on the Main Line—a far more upscale area. I saw the same projector, at a higher price. I pointed that out to the salesman. He admitted that Sears adjusted its prices based on the income of the neighborhood around its stores. (Apparently not enough to save Sears).

Infinite price adjustments as AI gets more involved

My long-ago lesson on pricing at Sears will become—has already become—commonplace place with the increasing application of artificial intelligence tools.

Back in 2015, for example, The Princeton Review was caught charging higher prices to students who lived in zip codes with large Asian populations. Since then, the data that can be used to customize prices have become more fine-grained. Why do you think every brand suddenly has an app? Because if you download the Starbucks app, say, the company can access your address book, financial information [that is, your credit card], browsing history, purchase history, location—not just where you live, but everywhere you go [if you have that feature turned on in your Settings]—and “audio information” (if you use their voice-ordering function). All those data points can be fed into machine-learning algorithms to generate a portrait of you and your willingness to pay. In return, you get occasional discounts and a free drink on your birthday.

We are entering an era of hyper-personalization—price discrimination on steroids.. Using data from our past purchases and some personal traits such as gender, we will receive product recommendations and pricing fine-tuned to our unique preferences and shopping habits. An airline would know the different values that a business traveler with a meeting scheduled in Chicago would have a higher willingness to pay for a ticket than another customer logged on at the same time but has the profile of a leisure traveler.

Of course, this is already the case, though more intuitive than data-driven. One reason many of us find buying a car distasteful is the process by which we feel we have to negotiate with the salesperson to get the “best” price. A good one observes the car we drove in with, how we’re dressed, even how we express ourselves and can calibrate the price accordingly.3 An algorithm will consider far more variables in suggesting a price.

Adam Elmachtoub, an associate professor of engineering at Columbia who studies pricing and fairness (he also works for Amazon), told me that personalization can be good or bad for consumers, depending on how you apply it. “I think we can agree that if personalized pricing worked in a way that people with lower incomes got lower prices, we’d be happy,” he said. “Or we’d say it’s not evil.”

We probably all agree that universities offering financial aid to students in varying amounts based on need is a positive use of personalization and price discrimination: same education, different prices. University of Chicago economist Jean-Pierre Dubé, holds that “personalized pricing should benefit the poor overall, since, in theory, people with less money would exhibit lower willingness to pay. By and large, when you personalize prices, the lowest-income consumers are getting the lowest prices…”

Let’s go back to the hand sanitizer during a pandemic, but switch to online shopping rather than at a store. Applying AI would determine that the home health worker would not pay $15, but calculates she would pay $6. She gets her sanitizer. It would estimate that Don, the restaurant owner, and Janice, with the day care, were likely to pay $15, or more. The other customers who looked but didn’t buy at $15 could be offered individualized prices that fit their willingness-to-pay profile, all in the context of the amount of inventory available.

How much do we value our privacy?

Striking the right balance between personalization and customer privacy is an ongoing challenge. Paying by credit card gives the banks and processors an in-depth look at our purchasing behavior and preferences. With E-Z Pass (or local equivalents) we leave behind travel breadcrumbs. Indeed, those indispensable mobile phones connect with cell towers and Wi-Fi routers that create a map of where and when we go, where we stay, and for how long. Are we prepared to give any of that up? All of the above, by the way, have been useful for catching and convicting criminals, too.

For most of us, most of the time, it’s likely that the benefits will outweigh the admitted downsides. For my part, I reject tracking “cookies” when offered the option in those annoying pop-ups on Web sites. On my phone, I make sure location sharing is on only when using apps that need it, like Google Maps. But that still leaves lots of digital dandruff that AI algorithms can play with. It’s a typical Pancake dilemma. I just hope I get some good prices when I get my next JetBlue ticket to Philadelphia.

Discrimination is a critical concept. It often has a negative connotation because it may associated with racial or gender discrimination, for example. But discrimination between hot and cold is important, or between a well-made product or a look-alike inferior knock-off. Coaches have to discriminate among players who they think will create the strongest team. As a teacher, I’m constantly having to discriminate between a written case analysis that might be a B+ or an A-.

I don’t mean to suggest the shopkeeper is an economist, thinking about market efficiency. She may just be taking advantage of the shortage. But the effect is the same.

Not that I buy a car often, but when I do I’ve taken to parking a block from the showroom and wearing some rumbled clothes. I can’t say whether that has had any effect.

Hi Ben interesting post. I loved the term”digital dandruff “.just to let you know the read portion says price discrimination but is last weeks essay on should I go to college. We listened on our way home from NH and we thought it sounded familiar but when I went to the written version it was about price discrimination. Maybe substack goofed? Sue

Ben,

Having just returned from my Denver classmate reunion I noted the various prices we all paid for our hotel rooms. Pricing on the Hilton website versus Expedia. In the end the difference was the cost of a modest meal.

Jeff