What if da Vinci had explained the Mona Lisa?

Should artists tells us what they want us to see in their creations?

I’ve noticed that in many exhibits of modern art, each work has next to it an exhibit label that, besides identifying the work and the artist and date, offers a paragraph describing the work, such as the example below.

In many cases the artist or sometimes an “expert” tells us what the work is about, and what we should see in it. I don’t recall that Rembrandt or Cézanne provided such commentary for each work. It is up to individuals to speculate and debate what the art is about.

Meet Madam Lisa Giocond

In that vein, consider what we’d have to think about the Mona Lisa if da Vinci had written an exhibit label explaining his thought process. Perhaps:

In my portrait of Madam Lisa Giocond, I wanted to capture her flirtatious naughtiness, with her teasing almost smile, part of the enigma of females. The illumination on her face captures the gaiety of women in general as well as the dark undertones of loneliness. All who know Ms. Madam Giocondo are aware that she uses her hands incessantly to gesture, so I painted her hands demurely folded as going against type.

Think of the centuries of unemployed art historians—and a different masterpiece on the wall of the Louvre— if da Vinci had explained what he was doing.

Anyone can be an art critic. Art appreciation is almost as personal as a fingerprint. I know what I like, you can tell me what you don’t like. We can never be wrong.

One of the most intellectually useful courses I endured as a student at Dickinson College was art history. We used Janson’s evergreen History of Art. After the course, I was able to at least understand what I was looking at when standing before a painting or sculpture at an art museum. I learned what made the Impressionists impressionist and Picasso had a Blue Period that gave way to his Cubist era.

I was mulling all this during my first visit to Boston’s Institute of Contemporary Art (ICA) since pre-pandemic. The ICA is a modernistic building in the burgeoning Seaport district, noted for “a dramatic folding ribbon form and a cantilever that extends to the water’s edge.”

As I ambled through an exhibition, pretentiously labeled “Taylor Davis Selects: Invisible Ground of Sympathy,” what struck me was the pomposity of many of the artists.

Exploring the “Invisible Ground of Sympathy”

Taylor Davis is an artist who was invited by the ICA to curate an exhibit drawn from its holdings. This is how the museum describes what makes this about an “Invisible Ground of Sympathy.”

Taking up questions of orientation, space, identity, and perception, Davis’s work insists on the unique sense of presence and attention that each viewer brings to an encounter with a work of art. Davis is conceiving of Invisible Ground of Sympathy as an open field in which a constellation of artworks are assembled to activate their different emotional and psychological intensities. Considering themes of precarity, wonder, violence, and beauty, and situating the viewer at its center, Davis presents a personal take on the ineffable complexity of making sense of the present, and of not having language for an experience in the moment.

Now, taking enough time, one could make sense of what these words mean individually.1 And I appreciate that she wants this to be about each viewer’s “unique sense of presence and attention". However, and maybe it’s just me, I didn’t get a connection between the world such as I inhabit and an “ineffable complexity of making sense of the present.” And, I don’t know, do the examples below leave you without “language for an experience in the moment?”

An artist may have all sorts of sources for inspiration. But, again, am I being boorish when I critique, not the art itself, not the skill that may have been involved in its creation, but in the presumptuousness of what it represents? For example, the photo above of a woman standing in the road with a suitcase is a screen grab from a movie. So in that context, we would know exactly why she is there. We are told on the exhibit label that “The scene is infused with foreboding.”

Turned away from the camera, with her arms crossed behind her back…the woman exudes a schoolgirl innocence and naivete that only heightens the uncertainty about her fate A network of unseen gazes…all situate the female figure as a passive object.

Or, sometimes, it is just a woman waiting for her ride.

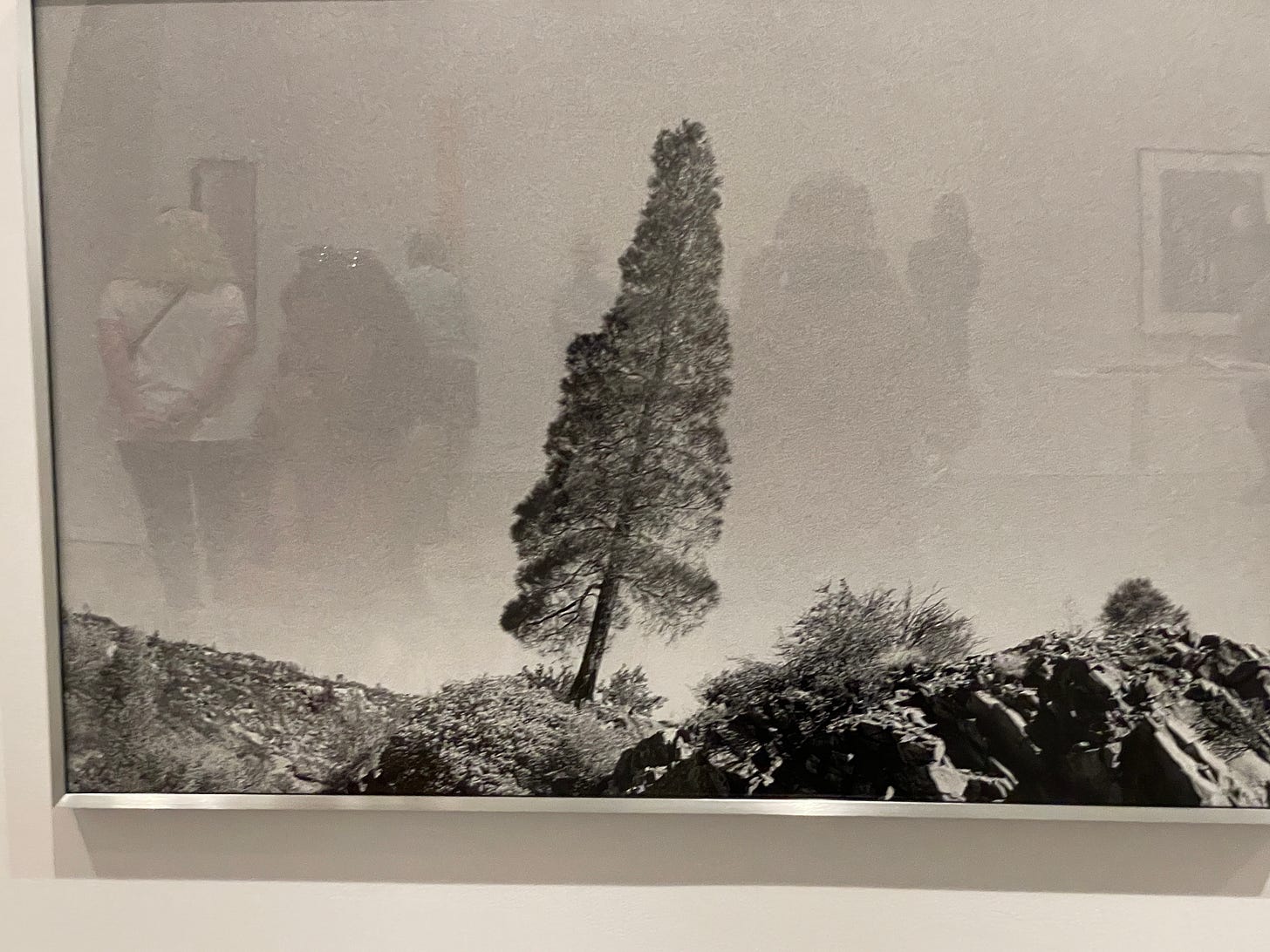

The above photo (the reflections are not part of the art) is Leaning Tree, by Shannon Ebner, accompanied by the above exhibit label. Reflect on it for a minute….. The label makes sure we know

she is interested in the ‘signal” sent by a leaning tree in an indeterminite landscape, a “place where an individual can fall out of circulation or where mobility and transmission can be impaired and disrupted, a place to receive error messages in the wild.”

Or, simply a place with no cell phone service—though in that case, we couldn’t receive error messages. Or is the error message something amiss with nature? No matter.

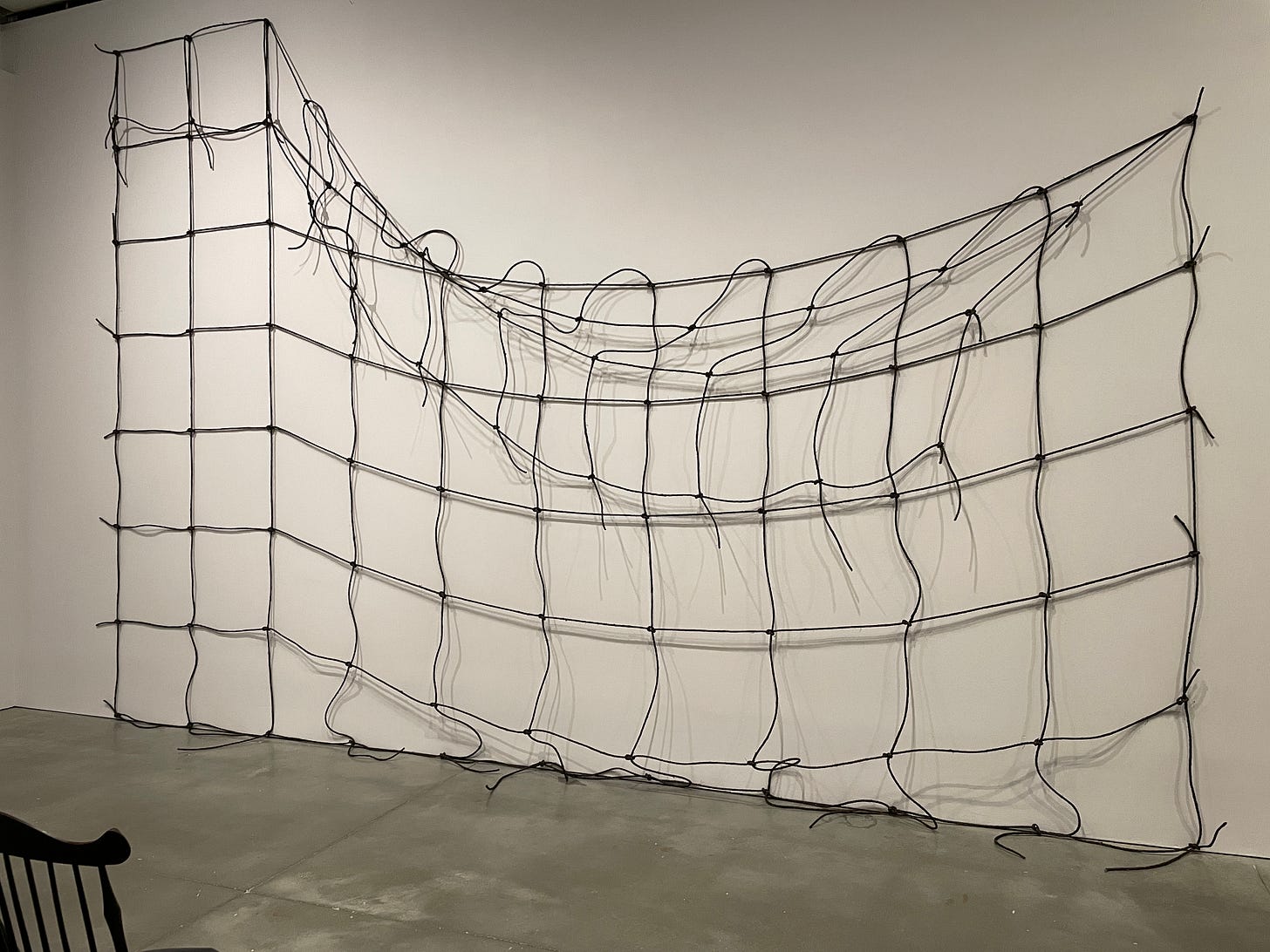

Two more examples. The above objet d’art is an untitled piece by Robert Rohm. The description adjacent to it says its creator “tacked a rectangular net along the perimeter of the wall and then removed the nails along the top and right edges.” He “anticipated this would result in a crisp diagonal as with a piece of paper.” Instead, he got what we see. This is presumably what makes this art, as “the material behaved contrary to Rohm’s prediction, introducing an element of chance.”

Or, he could have gauged the weight of the rope, adjusted for the impact of gravity, and “expected” what he actually got. Is art what happens when one makes a poor prediction based on ignoring available data?

One final entry at the ICA is a work in progress, “Piecing Together: bless our home go,” an unfinished embroidery from Venetia Dale. Writes Ms. Dale:

As a quiet protest to the expectation for productivity and completeness, the series Piecing Together embodies interruption in a way that expresses the connecting experience of something left unfinished. Each embroidery fragment is sourced from incomplete and hooked rug projects I purchased online….[T]he embroidery framed within tablecloths and runners connect each of these maker’s [sic] efforts at their places of pauses. These pauses give space to the stories that can be imagined in these fragments and serve as reminders to where and how value is placed on life’s quiet moments.”

For me, it is an enjoyable piece of art to view. But I suspect that no one who viewed this, absent Ms. Dale’s commentary, could tweak out the “pauses” and “stories” of works that were apparently unfinished. Maybe I should try cobbling together unfinished stories and articles I have started, and call them a novel of my pauses. James Joyce, anyone?

Let me be clear: I am not commenting on whether you or I or the many who walked through this exhibit, should like or dislike these or any pieces. Art they may be (though I reserve judgment on the slouching net). My reservation is with what the artists or those who speak for them think they are doing vs. what we see. It is what the artists hope we see in it vs. the remote possibility that any viewer will actually hit on it.

How does Abraham Maslow fit in here?

I suppose the upside is that I, you, and our society could devote some portion of time on earth to debating, pontificating, arguing about what is art, what is this art, who cares or doesn’t give a ——, is a positive sign of where we are in human development. Recall that psychologist Abraham Maslow proposed a hierarchy of needs as the basis for human development. Only when basic physiological and safety needs have been fulfilled do we have the luxury of seeking to satisfy higher-level needs, such as for love and belonging, self-esteem, and, maybe, self-actualization. I doubt if these artists would be indulging in their craft, I would be writing this, or you reading this, if we hadn’t moved well up that pyramid of needs.

I did struggle briefly with “precarity.” A Google search helped.

In fairness, many of a museum's accompanying notes provide valuable historical context and background information about the work itself rather than the pretentious comments you mention.

Dear Mr. Pancake:

While your critique of art museum commentary makes most of the points that should be made in any dismissal of this presumptuous practice you omit one: reading those postings induces eye strain and enhances the inevitable fatigue one suffers in a visit to any collection of paintings and sculpture. R. G. Freeman