Why we are a long way from eliminating fossil fuels

Even the most optimistic projections of renewal development fuel the conclusion that we are going to have to deal with large-scale use of fossil fuels for decades.

If you are of the persuasion that millions of Teslas, Volvos, and Freightliners replacing gas-burning cars and semi-trucks will make much of a dent in carbon emissions, think again. Fossil fuels are going to be with us in substantial quantity for decades.

True, renewal energy has been growing at a prodigious rate. But so has both global and U.S. energy consumption. Moreover, there is an inevitable cap on the amount of solar and wind capacity. Barring a rapid ramp-up in nuclear generation or a breakthrough in new technologies, such as fusion, fossil fuels will be needed in quantity for decades, at least.

The top-level projections for global energy use over the next 25 years account for the growing population and rising prosperity in developing nations, which will combine to create energy needs that will outstrip the capability of clean energy sources.

Global electricity demand will nearly double.

Energy demand for transportation will grow by more than 20%.

Energy demand for industry is projected to grow by 20%.

In 2010, 79% of the global energy mix came from fossil fuels. The UN-affiliated World Energy Council estimates that under its most optimistic scenario, a global consensus on driving environmental sustainability, fossil fuels would still account for 59% of energy use. In what I would consider its more pragmatic scenario, with a consumer focus on achieving energy access, affordability, and supply quality, the share of fossil fuels would be 77%, almost unchanged from 2010. This is despite expected steep improvements in energy efficiency and substantial increases in renewal energy sources.

Why will the world continue to require large quantities of fossil fuels? When we think about clean energy, for the most part, this relates to electricity generation with wind, solar, hydro, and nuclear. However, there are major energy consumers for which electricity is not a likely substitute with the current or foreseeable state of technology. For example, transportation accounts for 27% of energy use. Planes and ocean-going shipping alone account for about 5% of global energy use. Neither mode is a candidate for cleaner fuels over the next few decades. Electrifying freight rail lines, also fossil-fuel dependent, are not clean energy candidates.

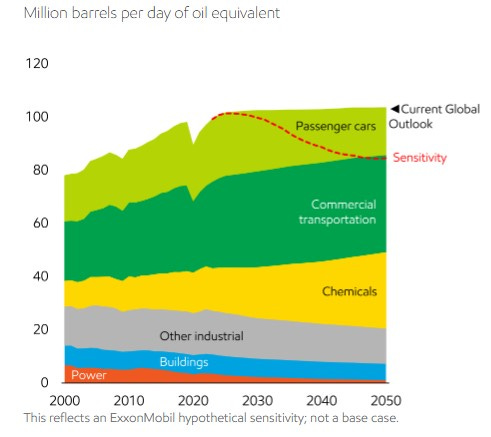

Exxon Mobil forecasts continued growth in all sectors of transportation other than light duty, which refers to cars and pick-up trucks.1 The projection expects a decrease in this category due to increased efficiency plus electric-driven vehicles. However, even as EV sales increase, it takes 10-15 years for the passenger car fleet to turn over. Therefore, internal combustion engines will continue on the road beyond 2050.

Electricity demand grows

Beyond transportation and its need for fossil fuels, the demand for electricity continues to grow. The U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) data shows that while solar and wind have grown substantially in percentage terms, their overall contribution to electricity generation has been modest. The chart below may be hard to read. It does show most noticably that coal has seen a steep fade, with natural gas assuming its previous role as the largest source of generating power. Nuclear power, which, until recently, the U.S. and Europe have been shutting down, is now the second largest source of electricity.

Zooming in just on the U.S., EIA projections to 2050 in the chart below find a continued reliance on natural gas but more than a doubling of renewables (half of that solar, about a third from wind, and most of the rest from geothermal and hydroelectric). EIA expects global electricity generation fuel sources will be in similar proportions, with renewables plus nuclear at about 56%.

That said, EIA projections highlight a key global insight—global energy-related CO2 emissions will increase through 2050 in all scenarios it parses except its Low Economic Growth case.

Our projections indicate that resources, demand, and technology costs will drive the shift from fossil to non-fossil energy sources, but current policies are not enough to decrease global energy-sector emissions. This outcome is largely due to population growth, regional economic shifts toward more manufacturing, and increased energy consumption as living standards improve. Globally, we project increases in energy consumption to outpace efficiency improvements. [My italics added]

Putting this together, all the global policies trying to reduce carbon emissions in the cause of slowing (not even reversing) climate change are not going to work. In part this is actually a piece of a good news story. Although carbon emmission-free energy sources will be an increasing proportion of total energy needs, the total need for energy is increasing in large measure due to economic progress globally. While fossil fuels decline in proportion to total needs, in absolute meaures they will be as much as or greater than they are today.

The chart below projects that 2050 the need for petroleum alone will be about the same in 2050 as it is today, unless ALL passenger cars are electric by then (the dotted red line). That is considered highly unlikely.

Formidable barriers to replacing fossil fuels

Baked into these projects that look out 25 years are the many hurdles in front of creating fossil fuel replacement infrastrucure at scale. A report from consultants McKinsey & Company highlighted that “successful renewables developers must navigate an increasingly complex and competitive landscape.” Developer Vineyard Wind noted, “Offshore wind projects are subject to permitting, review, and consultations with nearly 30 different agencies at the federal, state, local, tribal, and regional levels. Each public agency’s permitting process includes opportunity for public review and comment.”

Cape Wind, a massive 1500-gigawatt wind farm proposed in Nantucket Sound in 2001, off the coast of Cape Cod, took nine years to obtain all its permits and approvals from Massachusetts and the federal government. Its original developer abandoned it in 2017. Vineyard Wind resuscitated the project and began construction in 2019, with the first power trickling out in early 2024.2

McKinsey found another hurdle in looking at projects for Germany that could apply elsewhere, available land.

Developers are in a constant scramble to identify new sites with increasing speed. Our analysis in Germany, a country aiming to nearly double its share of electricity coming from renewables by 2030, offers a glimpse into the constraints. Of the 51 percent of the country’s land that is potentially suitable for onshore wind farms, regulatory, environmental, and technical constraints eliminate all but 9 percent.

Even in what would seem to be the wide open spaces of America’s West developing large scale projects meet blowback from environmentalists and communities3:

Esmeralda County, Nevada, one of the most sparsely populated regions in the nation, is at the center of a growing debate over a proposed solar energy project that could become the largest in North America.

The proposed solar project, if approved, would cover an area roughly the size of Las Vegas, right in the heart of Esmeralda County.

Many residents are concerned that the construction of this solar project would lead to the loss of the county’s natural beauty, which they believe should remain untouched. The land designated for the project is largely undeveloped and was once considered for state park status.

The implications for climate change

Of course, the reason why we delve into this at all is because of the implications of burning fossil fuels for the impact of carbon emissions and the climate. Previously, I proposed that while there is a climate problem, this is not worthy of the label of “crisis.”

Let me be VERY clear: there is irrefutable evidence that the global climate is currently warming. But given how this is somewhat predictable, gradual, and the effect likely to be incremental and spread out over decades, it might be more appropriate to call this a problem. Or an issue that needs to be addressed. But not a crisis.

In this regard, I find myself an uncomfortable bedfellow with President-elect Trump’s nominee for Secretary of Energy, Chris Wright. The CEO of oil-field services company Liberty Energy, Wright, has said

“fighting climate change is less important than allowing the world’s poorest to improve their lives by burning oil and gas. The benefits of cheap and reliable energy, he argues, more than outweigh the costs of climate change.”

“A little bit warmer isn’t a threat. If we were 5, 7, 8, 10 degrees [Celsius] warmer, that would be meaningful changes to the planet,” he said in the PragerU interview.

I don’t want to re-litigate the broader climate change issue here. My larger point is that, even with due diligence in aiming for cleaner sources of energy, we are going to have to deal with large-scale use of fossil fuels for decades. The Trump Administration’s “drill baby drill” attitude will only be a blimp in the larger scheme of the forces requiring continued drilling, no matter whose policies predominate.

I know—depending on Exxon-Mobil for my data? However, it has a stake in trying to devise projections as accurately as possible on which to base its strategy for petroleum production as well as investment in what may be replacement products.

Shortly afterward, one of the massive 300-foot-long fiberglass blades fell apart, littering Nantucket beaches with dangerous debris. Generation and construction were halted while the mess was cleaned up and the cause investigated.

See the August 14, 2023 Pancake: “Can you be an environmentalist AND an alternative energy advocate?”

Sad, but mostly true. While there may not be a climate crisis per se (my son would vehemently disagree), it could easily be if urgent action is not taken to put in place policies that will accelerate the process of reducing the need for petroleum-based products. The clock is ticking.

Unfortunately this is a very cogent and persuasive argument. Even continuing increases in temperature at 1 or 2 degrees has consequences.( Maybe a problem and not a crisis. )

However perhaps we need to be talking once again about reducing population growth? Remember ZPG?